HARQUITECTES . photos: © Adrià Goula

No context is irrelevant to a new building. And often the site itself generates conditions affecting the project in almost every decision. This is not the case with this house.

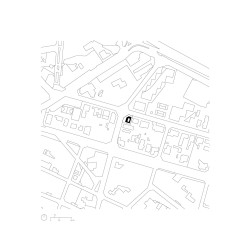

The sun, the geometry of the plot -almost square with a chamfer-, a neighbour too close to the south, and a tower of houses to the north, more typical of a residential area of the sixties than of this piece of garden city where the plot is located. Four badly counted inputs.

The owners (a couple with two children) wanted a house without maintenance, with a lot of privacy and a good relationship with the garden -more like a courtyard- all year round, a well-placed studio, and a few other usual requirements. And a desire to live in a modern house -without a capital letter-. And a certain interest in contemporary Japanese domestic architecture.

With these determining factors, it was clear to us that history had to be written almost from scratch, or rather from within, with the building itself. A new site had to be created.

The plot was flat, slightly below street level. No trees.

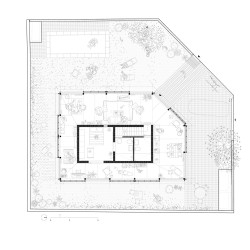

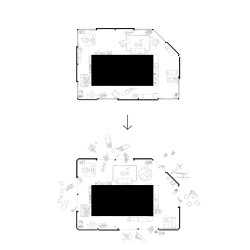

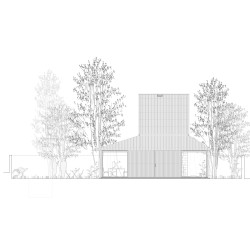

The first step was to build an opaque fence as high as possible, about two meters, and place the house off centred to the east, filling the 120m2 of maximum occupation and filling all the building limits except the west, where the sun comes in all year. There is where the perimeter garden becomes wider (7.6m), the rest has variable widths adapted to the regulations (3m to neighbours and between 5 and 6 to the streets) -the regulations force things that do not always make much sense-.

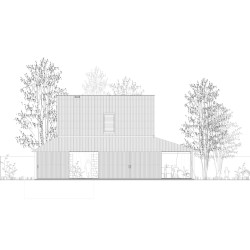

To the north we planted some evergreen trees that, with time, will deprive the view from the neighbouring tower of houses.

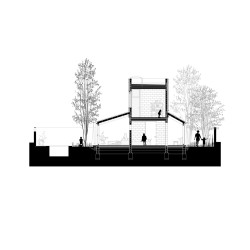

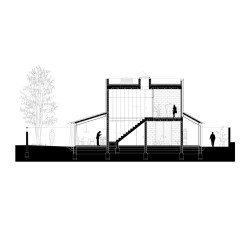

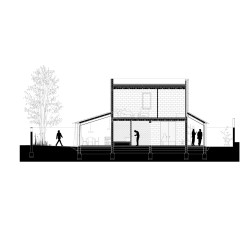

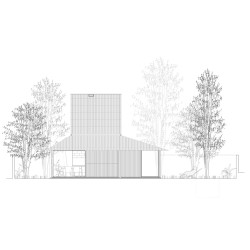

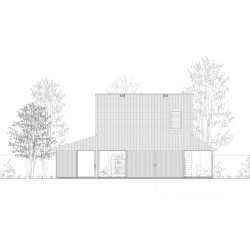

The new house is structured in four concentric layers parallel to the limits of the plot, like an onion. From outside to inside: the building fence, the perimeter courtyard and a continuous gallery that surrounds the central body, a two-storey concrete block box.

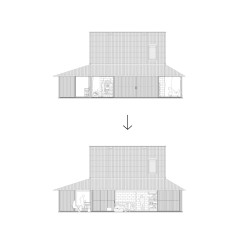

In the initial phases of the project, when the house was bigger, the perimeter gallery was an intermediate space, bio climatized, with complementary uses, and all the main pieces were housed in the core of the house. Later, due to budgetary adaptation, the surface was reduced and only the rooms, the bathrooms and the stairs were left in the central body. The common areas were moved to the gallery.

Almost everything happens in the gallery. It is a veranda, with certain resonances to Charles Moore’s Orinda house, which proposes intense and variable relations (seasonally) with the patio; in summer, through the large sliding walls it becomes a porch; in winter, large windows in the corners offer framed views of the garden and capture solar radiation to the west. Contrary to what is usual, in this house the windows are fixed, and the mobile doors are opaque, a condition that constantly transforms the facade and the gallery, depending on what is open and what is closed.

As in the chapel of Santa María dos Anjos by Lina Bo Bardi, the veranda, with its sloping roof, is built with light and dry systems: wooden structure (pillars, beams, and roof) and glass, aluminium, wood and corrugated galvanized sheet enclosures. In contrast to the lightness of the gallery, the central core is massive and compact, with more thermal inertia. The block walls and slabs are left visible in the gallery and painted white in the rooms.

In winter, the veranda shelters and heats the entire central body (bathrooms and bedrooms), which does not have its own climate system (on the ground floor); the concrete floor, with a lot of inertia, apart from receiving direct solar radiation on time, is heated via underfloor heating, as are the rooms on the second floor; generation is by aerothermal heat pump.

In summer, when the sliding doors are closed, the windows are protected from the sun by the overhang of the roof and by reflective exterior curtains. At the same time, the inclination of the roof favours, by stratification, a passive ventilation system that evacuates the hot air through four ducts hidden in the facades that work as small solar chimneys, favouring the natural renovation and facilitating the cooling of the veranda.

Ten years after the first meeting with the clients, and with a long and intense history in between, house 905 was completed. The long time was another determining tool in the process of the project.

Architecture sometimes takes advantage of (its) slowness.

_

HOUSE 905 // CASA 905

Site: Igualada, Barcelona

Architect: HARQUITECTES (David Lorente, Josep Ricart, Xavier Ros, Roger Tudó)

Collaborators: Blai Cabrero, Jordi Mitjans, Montse Fornés

Team: Carles Bou (Quantity Surveyor)

Project years: 2012-2017

Construction years: 2017-2020

Built area: 154m2

Photographer: Adrià Goula

Ningún contexto es irrelevante para un nuevo edificio. Y a menudo el propio sitio genera condicionantes, afectando el proyecto en casi cada decisión. No es el caso de esta casa. El sol, la geometría de la parcela (casi cuadrada con un chaflán), un vecino excesivamente cercano a sur, y una torre de viviendas a norte, más propia de un polígono residencial de los sesenta que de este trozo de ciudad jardín donde se ubica el solar. Cuatro inputs mal contados. Los propietarios (una pareja con dos hijos) querían una casa sin mantenimiento, con mucha privacidad y una buena relación con el jardín -más bien un patio- durante todo el año, un estudio bien puesto, y otros pocos requerimientos habituales. Y ganas de vivir en una casa moderna -sin mayúscula-. Y cierto interés por la arquitectura doméstica japonesa contemporánea. Con estos condicionantes teníamos claro que la historia había que escribirla casi desde cero o, mejor dicho, desde dentro, con el propio edificio. Había que crear un sitio nuevo. La parcela era plana, ligeramente por debajo de la rasante de la calle. Sin árboles. El primer paso fue construir una valla opaca lo más alta posible, de unos dos metros, y situar la casa descentrada hacia el este, colmatando los 120m2 de ocupación máxima y rellenando todos los límites edificables excepto a oeste, por donde entra solo durante todo el año. Allí es donde el jardín perimetral se hace más ancho (7,6m), el resto tiene anchuras variables adecuadas a la normativa (3m a vecinos y entre 5 y 6 a las calles) -la normativa obliga a cosas que no siempre tienen mucho sentido-. A norte plantamos unos árboles de hoja perenne que, con el tiempo, privarán la vista desde la torre de viviendas vecina. La nueva casa se estructura en cuatro capas concéntricas paralelas a los límites del solar, como una cebolla. De exterior a interior: la valla de obra, el patio perimetral y una galería corrida que rodea el cuerpo central, una caja de obra vista de bloque de hormigón de dos plantas. En fases iniciales del proyecto, cuando la casa era más grande, la galería perimetral era un espacio intermedio, bioclimatizado, con usos complementarios, y todas las piezas principales se alojaban en el núcleo de la vivienda. Posteriormente, por adecuación presupuestaria, se redujo la superficie y en el cuerpo central sólo quedaron las habitaciones, los baños y la escalera. Las zonas comunes pasaron a la galería. En la galería pasa casi todo. Es una veranda, con ciertas resonancias a la casa de Orinda de Charles Moore, que propone relaciones intensas y variables (estacionalmente) con el patio; en verano, mediante los grandes paramentos correderos se convierte en un porche; en invierno, grandes ventanales en las esquinas ofrecen vistas enmarcadas al jardín y captan radiación solar a poniente. Contrariamente a lo habitual, en esta casa los cristales son fijos y los portones móviles son opacos, una condición que transforma la fachada y la galería constantemente, en función de qué está abierto y qué cerrado. Como en la capilla de Santa María dos Anjos de Lina Bo Bardi, la veranda, de cubierta inclinada, se construye con sistemas ligeros y en seco: estructura de madera (pilares, vigas y techo) y cerramientos de vidrio, aluminio, madera y chapa galvanizada ondulada. En contraposición con la ligereza de la galería el núcleo central es masivo y compacto, con más inercia térmica. Los muros de bloque y los forjados se dejan vistos en la galería y se pintan de blanco en las habitaciones. En invierno, la veranda abriga y calienta todo el cuerpo central (baños y habitación), que no tiene sistema de climatización propio (en planta baja); el pavimento de hormigón, con mucha inercia, aparte de recibir puntualmente la radiación solar directa, se calienta vía suelo radiante, al igual que las habitaciones del primer piso; la generación es por bomba de calor aerotérmica. En verano, cuando las correderas están cerradas, las ventanas se protegen del sol con el vuelo de la cubierta y con unas cortinas reflectantes exteriores. A su vez, la inclinación del techo favorece, por estratificación, un sistema de ventilación pasivo que evacúa el aire caliente mediante cuatro conductos ocultos en las fachadas qué funcionan cómo pequeñas chimeneas solares, favoreciendo la renovación natural y facilitando el refrescamiento de la veranda. Diez años más tarde de la primera reunión con los clientes, y con una larga e intensa historia entremedio, se completó la casa 905. El largo tiempo fue otra herramienta determinante en el proceso del proyecto. La arquitectura, a veces, saca partido de (su) lentitud.