architecten de vylder vinck taillieu . photos: © Filip Dujardin

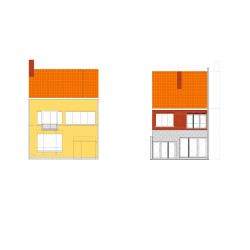

This is the facade. And the facade is this. The front door is facade. And the superstructure is facade.

And there are windows in the facade. They were there already.

RESIDENCE

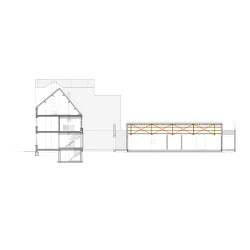

The residence won’t be much different. But, as it is, needs extra stability. And extra stability already;

then different possibilities for establishing connections between rooms.

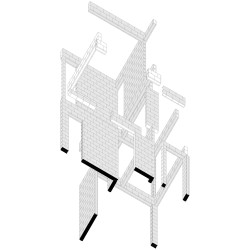

A study is wooden supports. A study in brick. That is to say: beams and columns in brick. That’s it.

Guistavino Vaulting.

It is often impossible to learn what intentions it served. Was it for living in or for utility? Often the present user or resident knowsscarcely anything about what purpose the previous occupant, let alone the very first, had for the building.This is not always so – sometimes it is perfectly clear – but sometimes it is impossible to find out.

How it was built is often even less clear. Apart from style (that is, vision), pure or historically assured, buildings are often subject to poorly thought-out principles or completely isolated modifications. Even trying to investigate the building does not eliminate risk: after all, the situation is sometimes so unclear that even dismantling depends on guesswork.

It may prove possible to discover what the purpose was and how it was built, or maybe not. In either case, it can happen that a building has no identity whatsoever. There is no place to start, no special detail which catches the eye. But still, they are not “lesser” buildings. Maybe buildings like these even have “more” prospect of future significance. There is a building – and so there may be a certain constraint, but also a certain freedom. Strange: freedoms quite often emerge as a consequence of limitations.

The house is located on what was once an anonymous main road. The project immediately takes the name of the alley at the back. Hence a first name is given. It is a sign. The building is constructed partly of thin concrete-like blocks. The walls feel brittle. Earlier modifications do not seem to have been considered properly in the context of the whole building.

The concrete floors are thin. The structure of the building may thus be termed dubious – as regards the present condition of this house, as well as an imagined future for the house. But it’s a pleasant

house. The architecture dates from somewhere in the 1930s.Yellow brick and wide windows with slender metal frames give the house a somewhat optimistic look. Maybe not too much should be changed; or just the configuration of the rooms. It is as though one had to entertain doubts about concrete.

The walls, the blocks. The floors, the vaults. Nonetheless, it seems appropriate to introduce a structure of columns, beams and walls made of concrete blocks. Blocks with a relatively rough finish alternating as wall or structural element. But especially that: beams and columns in masonry. Every modification – closing off a door, making an opening, reinforcing a wall lengthways or supporting a floor halfway – done in the same fashion. It is as though it were a 1:1 drawing of countless separate decisions. Apparently.

But at the same time merging into a whole: the masonry does its work; gives it a certain abstraction but also a strange poetry. It reveals nothing other than the original structure of the building:where the building was unsatisfactory, and where it was now modified, all made visible in the material of which it consists.

And furthermore: white. White as a sheet of paper for the drawing of the blocks and the modifications.

Exposing what is going on is a leitmotif, as in many projects, but never a goal in its own right. The estrangement of column, beam and wall by brickwork causes the pure analysis, which becomes a synthesis, to become readily visible. The strangeness that besets the perception raises the prospect of aesthetic pleasure. White plasterwork is the best background for this, like the white space between lines on a page.

The front facade becomes the front facade. The previous door remains a door, but stone strips draw lines that make it merge into the background of the facade. The bathroom on the top floor rises through the roof, but aligns smoothly with the front facade.

_