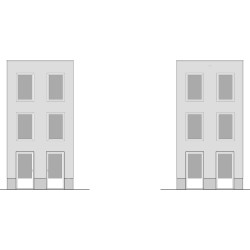

21 building plots have been assigned for private development on a spit of land in the former Rotterdam harbor area. Within a number of fixed architectural guidelines, a huge diversity of properties is being built. The design for the house on plot 7 is intended to demonstrate that maximum contrast can be achieved using minimum means. The design is discreet and deviates from the other houses, which incorporate a wide variety of forms and materials. In addition, the layout is intended to be flexible. The design of the façade is, therefore, abstract and not a translation of specific interior components. This abstraction is carried through as far as possible by avoiding particular details and elements that make the scale immediately apparent.

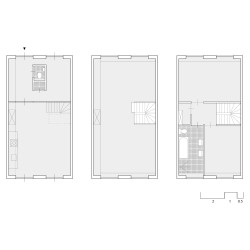

The design strives to allow its generous approach to space to be the principle quality of the building. This is interpreted in the shell by means of high ceilings, large openings in the façade, and the absence of structural elements on the interior.

_

In our design for the private residence in Katendrecht the generic predominates. In essence this house also functions as a ‘solid’. The interior has been made as flexibly divisible as possible, drawing a clear distinction between the permanent

elements, such as the stairs and the structure, and the temporary elements, such as the kitchen, the bathroom and the room partitions. In this project, the choice of the generic is born out of the realization that a ‘surfeit of specificity’ reigns in its surroundings. The house is part of a gentrification project in the socially and economically deprived area of Katendrecht, Rotterdam. This project consists of a long row of ‘free parcels’ and is based on the idea of a motley collection of variations on the ‘urban dwelling’ type. The result looks like a ‘dog run’ for architects. There has been an unbridled application of design resources. The dwellings lack any kind of mutual coherence. Everyone is trying to out-shout everyone else, so that hardly anything can be heard. In response to this environment we opted for a circumspect attitude – by concentrating on the generic qualities of a home. This dovetails

with the strategy of Austrian architect Hermann Czech, who in his collection of writings entitled Zur Abwechslung (For a Change) advocates a ‘silent architecture’, which ‘speaks only when it is asked something’ 1) Thus in this context, it is in fact ‘the shock of the normal’ that is aspired to with the house in Katendrecht – in a way similar to that cited by industrial designer Jasper Morrison in the book Supernormal: ‘by making an object so “normal” that it is normal no longer, it becomes simultaneously “normal” and “extraordinary”.’ 2) The analogy-based approach, in the case of the house in Katendrecht, lies in the appeal made to collective memory: which elements and proportions identify a building as a dwelling? And at what point does the balance between specific and generic tilt too far towards the generic?

In addition to the circumspect attitude we chose for this project, the ‘limitation’ of

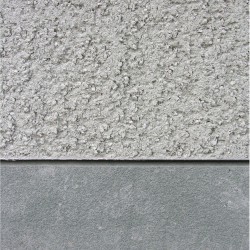

design resources forms an important motive. That is to say, what is the least amount of resources necessary to design a normal and proud house? The tendency towards limitation comes out of the conviction that sufficiently rich variety lies in the basic elements of architecture. The toolbox of every designer contains ample variety in and of itself: the arrangement and proportions of openings, walls, roofs and floors. This represents an inexhaustible fount. Solving design problems with only the basic elements mentioned is a challenge. We do not allow ourselves to evade the discipline of architecture and take refuge in ‘metaphors’ borrowed from other disciplines. As far as we are concerned, architecture is indeed an autonomous language. In principle, we conform – in an abstract sense – to the rules of a built environment. Again, the degree of abstraction can vary with each project. One salient example is the Haus Ohne Eigenschaften (house without characteristics) by O.M. Ungers – because of the balance achieved between the generic and the specific: the edifice remains, in spite of the radical abstraction, clearly identifiable as a home and yet is generic enough to be able to take root in multiple settings. In the case of the house in Katendrecht, ‘the window opening’ was chosen as the dominant element.

By confining ourselves to this basic architectonic element, we can in fact make a generic building specific. The character of the house is primarily defined by the window type and its proportions. The windows are made vertical, so that the light can fall deep into the house. The piers that were formed by doing this also provide a certain shelter. The regular vertical grid of windows and the generous ceiling heights were a deliberate connection, albeit in an abstract sense, to the typology of a townhouse. There is a deliberate disorientation concealed in the proportions of the windows. Without size references, the aspect of the house meets normal expectations, but everything turns out to be one and a half times as large.

This results in a subtle confusion in scale: the door handle ends up at a height of

1.5 m.

THE SHOCK OF THE NORMAL: A HOUSE IN KATENDRECHT

Excerpt from article in OASE journal for architecture, written by Monadnock

_

HOUSE IN KATENDRECHT

CLIENT: KATRIJN VERSTEGEN AND SANDOR NAUS LOCATION: ROTTERDAM / THE NETHERLANDS PROJECT TYPE: SINGLE-FAMILY HOUSE

YEAR: 2005 – 2008

STATUS: COMPLETED