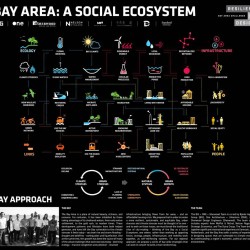

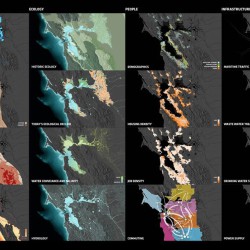

The Bay Area is a place of natural beauty, richness, and resource. For centuries, it has been inhabited by those taking advantage of its sheltered waters, from early native settlement, to the gold rush, to modern times. These development patterns and lifestyles have both helped generate, and have left the Bay vulnerable to the climate stresses it feels today – sea level rise and storm flooding – drought and wildfires – earthquakes and liquefaction. And at the same time, this growth has been the source of many of the urban challenges that we know now today – declining ecology – massive congestion and pollution – strained infrastructure bringing flows from far away – and an affordable housing crisis.

_

·

Overall Regional Approach

We propose that in order to create a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable Bay, urban stresses and climate stresses must be thought of as one – and in order to work on these issues, we must break the traditional silos of city-making – thinking of the Bay as a Social Ecosystem, one where, rather than working as opposing forces, ecology, people, infrastructure, and mobility work together, as self-reinforcing systems. For our regional approach, we propose a series of bay-wide strategies that can work in concert to build a more resilient bay:

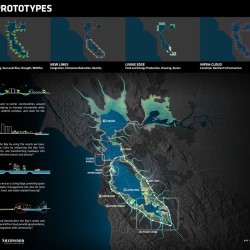

The Bay’s once prominent creek system, a balanced machine for stormwater management and wildlife movement, has been culverted, narrowed, and buried over decades – and is now showing itself again, as areas of high flood risk and liquefaction. Can we naturalize and re-center communities around new Hyper-Creeks, helping to manage stormwater while providing firebreaks, wildlife corridors, and room for the Bay to grow?

The car-culture of the 20th century has rendered vast swathes of the Bay impermeable, preventing aquifer recharge and limiting use to parking. As autonomous vehicles are adopted, can we peel back decades of paved-over surfaces, improving water absorption and fighting drought, while providing much needed space for affordable housing as part of a Green Grid?

Traffic has increased by 80% in the last 10 years, and traditional, heavy transit is difficult to reach and costly to upgrade. Can we re-connect the Bay by using the assets we have, creating flexible New Links by enhancing the Bay Trail, expanding ferry service, and transforming roadways into efficient routes for collective transit and density?

Currently slated for tidal marsh restoration, many of the Bay’s iconic salt ponds will be under threat from sea level rise and lack of sediment flow. Can we re-think these area as a Living Edge, providing space both for nature and water management but also for local production of energy, food, and badly needed housing?

The Bay Area is dependent on vulnerable large-scale infrastructure systems – its drinking water, electricity and food imported across long-distances at great expense. Can we modernize and decentralize the Bay’s water and power supplies into a local Infra-Cloud, providing redundancy, sustainability, and integration with community?

In light of climate change and sea level rise, can we not just save the Bay – but can we grow the Bay, for nature, for people, and for a changing climate?

_

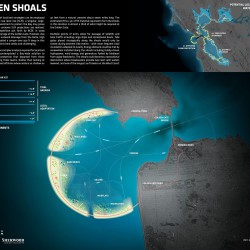

Golden Shoals

Whereas a multitude of localized strategies can be employed over time to adapt to sea level rise (SLR), a singular, large-scale infrastructure investment to protect the Bay may prove attractive if the more extreme SLR projections are realized. The Rising Tides competition put forth by BCDC in 2009 contemplated a tidal barrage at the Golden Gate. However, due to the tidal prism and outward drainage from the Delta, high velocity flows have created a canyon over 350 ft deep in this location. Such a deep barrage is not only costly but also presents numerous ecological and logistical challenges.

As a counterpoint to the complex analysis required for localized solutions, our team contemplated a Bay-wide solution to SLR that departed from those presented by the Rising Tides teams. Instead of looking at the Gate itself, we looked offshore where waters as shallow as 30 feet to form a natural crescent about seven miles long. The estimated 7M cu. yd. of fill material required to form the shoals in this location is almost a third of what might be required at the Golden Gate.

This 7-mile long crescent of underwater shoals could be transformed into a new, ecologically-attuned land mass. Multiple points of entry allow for passage of wildlife and boat traffic including cargo ships, fishing and whale watching boats and recreational sail boats. The shoals could become a recreational destination where breakwaters provide calm waters leeward and allow for exploration of a new reef ecology. The shoals would create swimming beaches – “Golden Gate Beach” – and wetland habitat – “Golden Marshes”. Structures such as cultural pavilions could be built along the shoal and into the calm water with wet feet.

As a jetty, the shoals could solve the problem of sand erosion at Ocean Beach, saving one of the region’s most popular beaches. Spanning from Ocean Beach to the Marin Headlands, the ocean side of the shoals creates one of the longest surf breaks on the West Coast!

Tide gates placed strategically along the shoals would only need to be closed during extreme tide events. During most events, terrestrial floodwaters from the Delta will be able to escape through the perforated shoals. As the ocean more frequently reaches problematic elevations, pumping requirements intensify. This energy demand could be met by renewables installed along the shoals including tidally-driven hydropower, wind energy and generators fueled by biodiesel from algae feedstocks.

Bridges from the shoals to land provide access from the Gate up and down the coasts where recreational ships typically enter and exit. An opening in the middle of the shoals provide access for logistics vessels including cargo ships and oil tankers. A dune walk provides accessible pathways for all Bay Area residents to enjoy, and would create a new recreational loop, linking the western edges of San Francisco and Marin.

_

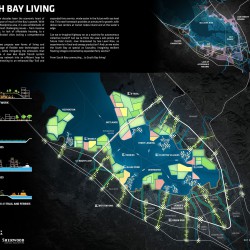

South Bay Living

South Bay creeks terminating in the Bay form a vast network of sloughs, mudflats and tidal wetlands, weaving through the area’s extensive and iconic salt ponds. The South Bay Salt Pond Restoration Project is the largest tidal wetland restoration project on the West Coast and aims to restore 15,200 acres of industrial salt ponds to a rich mosaic of tidal wetlands and other habitats, at great cost. However, tidal wetlands that cannot migrate upland to keep pace with sea level rise may be lost underwater – an issue made worse by lack of sufficient sediment flow. Can we be strategic about the way we invest in the edge, leaving room not only for nature, but for local food production, water rentention and treatment, energy generation, and badly needed affordable housing and connections to the water?

Productive ponds can begin as innovation test beds. Stormwater management, nutrient recovery for food production, energy storage through the management of tides, wind energy production, fabrication of materials needed for the new floating structures will provide ecosystem services and bring new jobs to the South Bay. These localized energy, materials and water flows will build resilience into the existing centralized infrastructure by providing increased redundancy and, as a result, reliability. Areas with easy access to deep water channels and ferry access can become nodes of density for resilient, floating villages – creating space for up to 75,000 units of housing, and a new lifestyle for the South Bay!

_

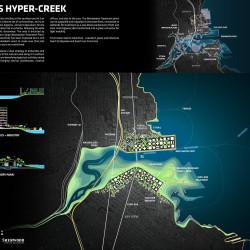

Islais Hyper-Creek

Islais Creek, emerging into the Bay at the southern end of San Francisco, sits between a diverse set of communities and is an important center of food, logistics, and port operations for the City. Flood risk is extreme, following the wide contours of the historic streambed and marsh. The area is encircled by heavy infrastructure and a large Wastewater Treatment Plant. Public access to the waterfront has been improved but is still limited, and Bayview residents want to make sure that jobs tied to industry are maintained.

For Islais Creek, we propose a dual strategy of protection and retreat – restoring acres of the natural creek along its southern bank, while protecting and densifying logistical activities along the northern piers – bringing vertical warehouses, creative offices, and jobs to the area. The Wastewater Treatment Plant is upgraded and migrated to the waterfront, connected to wetlands for treatment. And Highway 280 is transformed into a green connector for light mobility.

Hyper-Creek

We propose to give more than 300 acres back to Islais Creek to align the channel with its historical floodplain to the south, giving way to naturalized wetlands and making room for the Bay to grow. This partial retreat strategy will allow for adaptive management of coastal and fluvial flood risk and for new strategies to emerge for mitigating the risks of earthquakes and liquefaction. Creek naturalization throughout the watershed will provide increased permeability to slow terrestrial discharges by maximizing infiltration.

New Links

The restored riparian and upland areas will create green corridors that allow for ecosystem services and movement of wildlife and pedestrians. Widening the creek mouth will provide space for more tidal wetlands, offering protection, recreational space, and access to a natural Bay edge for residents. I-280 acts as a sky-connector, re-linking the Bayview neighborhood with areas north – while a dedicated cargo rail line might allow for the most polluting industrial uses in the area to migrate south along the Bay edge spanning from Candlestick Point to Brisbane Lagoon.

Maritime Edge

The 700 acres of industrial area throughout Bayview include approximately 13M sq.ft. of development with floor area ratios (FAR) ranging from approximately 0.3 to 0.8. This existing low density industry could be consolidated along the northern edge of Islais Creek by increasing FAR up to 5.0. This densification would offer up to an additional 5M sq.ft. (18M in total) of linked industrial use within San Francisco, while giving way for green infrastructure, open spaces, and a widened creek.

Infra-Center

With the redevelopment of Islais Creek, there is an opportunity to relocate the Southeast Wastewater Treatment Plant (SEP) and redefine the way water is managed in the City. We propose to transition the underutilized pier site spanning south of the creek to Heron’s Head as a new site for the SEP, it’s treatment processes re-imagined. Wastewater flows would be sent to a potable reuse facility, taking advantage of state-of-the-art anaerobic bioreactors to reduce energy demands. Flows that are not reused could be treated passively for nutrient removal via a living levee. This reimagined and publicly integrated WWTP of the future would build resilience into water supplies, making room for nature, for residents, and for the city’s continued growth.

_

_

BIG + ONE + Sherwood

The BIG + ONE + Sherwood Team is co-led by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), One Architecture + Urbanism (ONE), and Sherwood Design Engineers (Sherwood). The team also includes experts from Moffat & Nichol, Nelson Nygaard, Strategic Economics, and The Dutra Group.

Comments are closed.