AJDVIV architecten Jan de Vylder Inge Vinck . photos: © Filip Dujardin

The building was squatted. Part of it was destroyed by fire. Vacancy followed. The squatter came back. But even for the squatter there was nothing more to do. The fact that there was nothing more to do was not only the result of those last few years of impossible habitation, but even more the result of a perhaps impossible place.

A place with a history that could no longer be fully traced.

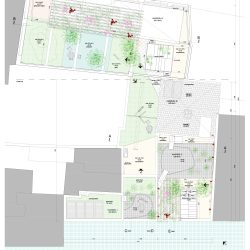

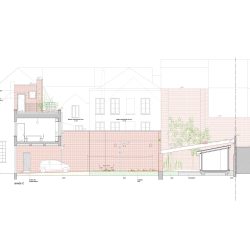

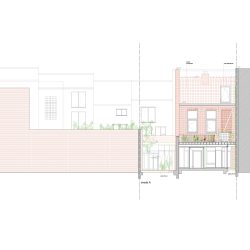

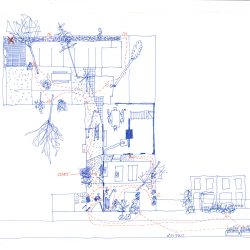

A small atelier. Withdrawn. Must have been two or three times as high. A narrow driveway to the back. With a small house on the side. But withdrawn too. Away from the street. And in between that house and the street, some outhouses. One next to the other. And a courtyard in between. On the other side of that driveway, a small building. What once might have been an office building. Three stories high.

The house must have been two houses once. Old dwellings of what should have been a monastery. Seventeenth century perhaps, the long bricks and the traces of rather steep roofs suggest this assumption. Parts of the high garden wall all around confirm it as well.

For the previous owner, everything was ready for demolition. But the permits could not be obtained. The previous owner could not solve the puzzle. The house changed hands.

We were happy with it.

How to live this. That was the question. Maybe the puzzle had already been solved. Just the way it all was. And understanding the way it still is. Nothing more or less.

Many angles. Many buildings. Many different parts, together as a whole. The atelier was really lost. The outhouses were burnt out.

Of the four distinct parts, two could be preserved. Two were replaced. But all this in the perspective of how it already was: a putting together of this and that. And that’s how it would be lived.

The house is the house where life would find its place. The front house, where the eldest children would be. A kitchen came in between. And in the vacant garden, a house to sleep in. In the attic of the house, there would soon be a place for the parents.

But in between all those houses: outside space. Except for a single greenhouse. All the new buildings separate from the garden walls. Separate from the existing buildings. Light all around, air all around. Children playing all around.

The sleep-house as a low shed, with small rooms and a bathroom. Taking a bath with open windows and seeing the morning light fall over your shoulders and onto the wall. A tent as its roof. The old beams of the former warehouse still hang in mid-air above. The building sits in the most southern part of the garden and enjoys the shade of the garden walls in summer. In early spring the sun falls between the sleep-house and the garden wall. Five windows draw in the light. In the evening they draw in the breeze.

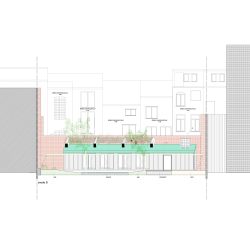

The kitchen becomes the centre. In the middle of the garden, to the side. With the garden in front.

Everything is glass. Except for the doors. In summer, the doors swing open. The space becomes something completely else. The small garden in front, between the small greenhouse and the garden wall with the street, has one tree. That tree blows high above. Shade and breeze. The rustling and tranquillity.

A small door on the side gives access to the street. Enough to put a chair out on the street and enjoy a late aperitif on Saturday. The sun in the west is setting in the street. While under that tree, morning coffee and silence.

The large – as far as large goes – greenhouse also sits separately and leaves open a narrow strip between the high garden wall. The greenhouse has a stove. For hot chocolate on Sunday evenings in autumn. Or to sit outside in spring for the first time. Between the glass of the greenhouse and the wall, an early summer breakfast.

In summer in the big garden – as far as big goes – the coolness under the plum tree. With ancient cobblestones underneath your feet. Old cobblestones on the roof of the sleep-house. Red flower pots along a path from front to back. Triangular terraces in between.

On the kitchen a blue terrace. A bathhouse in the future. On the roof of the front building, the last and highest terrace. A loggia. At the same height of the crown of that one tree in the front garden.

The house. And how to live it. It can be read by the places in between.

Each room becomes what is outside of its window. The tree outside. The table, the chair, the bed inside. Children jump from their beds into the garden and dig holes everywhere. Sometimes there’s almost no garden anymore. They climb on the roof and fall off, as they do in that young tree. And a rainwater pump to flood the garden from time to time.

When the garden becomes too small, the gate to the street opens. Sometimes just the hatch. Other times, the door as well. And when possible, the whole gate. Life moves toward the street. And onto the street. Children walk in and out. The neighbourhood. The summer. Another aperitif. At night the gate closes. The toys are left behind in the garden.

On the first floor of the house is a library. A big library. And yet too small. Books everywhere. With a large, square table. A table to draw on. Although, drawing happens all around.

In the room next to the library there is a small, yellow table. With a view of the garden. A table to write. Although, writing happens on tables all around the house. And in summer, in the garden. Not just to write. But also to draw. And every table serves as a place to eat. To eat together. To drink together. To live together.

The oldest children left the house. A moment. One of many moments.

The practice has returned home. The front house is now a small practice. A small architecture practice. At home.

It is a homecoming. It is different. It is everywhere. Immediate. It is free, yet persistent. And different. Different from when the practice was not at home. The house is now the practice. The practice, the house.

Yet the house has always already been the practice. Not only for drawing, but for every other moment too. For writing. Or for debating. And the house itself. How it was built. How it was lived. Eventually. First, the front house. Then, the house. Then, the kitchen and finally the house at the back. Everything in its time. Years. But everything as it happened. The life in one house puts the other in a different light. Continuous changes made how it is today – and what it will still become tomorrow – different than how it was intended.

Life made the house, or rather, the houses. As such, every house is different. The old houses. The new houses. And on their own too. The front house could remain how it was. The middle house had to be repaired and reinforced. A sequence of separate and ever-changing interventions are the measure for subsequent transformations. And even the transformations are transformed. Every new intervention canbe read.

Not just as intervention on its own. But as idea. As an idea of how such an intervention could have something to do with architecture. Materials and detailing. Yet, perhaps even without detailing. And just as it is. As the materials are what they are. And yet every intervention left on its own as intervention. To give a chance to the intervention to be more than mere solution. Rather not even as a solution. Nor an answer.

The practice has returned home. For only a moment. But a remarkable moment. The house shelters the practice. So that the practice may leave again. The practice needs shelter for some time. Because the practice needs something different for some time. Needs to find something different. Will find something different.

Different times are coming. Different needs need different practices. It is a simple question. But not an easy question. But a question that needs to be asked. A certain peace can be found at home. Yet an immediate energy too. Because even though less is wanted. It always becomes a lot.

Another practice. Another world. The house. Or rather, the houses. No better place.

And when the practice will leave again, then the house will open its rooms to life again. To the life of the house. Rooms for drawing. Definitely. Since drawing has always been part of the house. It started in the house. And will be in the house even more.

Or will the children soon be ready? Ready to make it their home? For the coming years? We’ll see.

A house needs to change. If it wants to be a home. To be able to come home. After having left. And to be able to leave again. ‘How to house life?’ Is still something else than ‘how to live a house?’

_