Atelier Kempe Thill . Canevas architecture et ingénierie . photos: © Ulrich Schwarz

The two apartment blocks Florair 2 and 3 are located in a hilly, park-like setting in the green Jette district of the Brussels metropolitan area. The surrounding neighborhood is characterized by urban perimeter blocks averaging four stories in height, a sports complex, and wide, avenue-like streets with large trees.

Integrated Modernity

The Florair ensemble encompasses a total of four approximately 100-meter-long, slightly shifted residential blocks, which are staggered uphill along the Avenue de Guillaume De Greef. The whole complex was designed by the architect Remy van der Looven in 1956 and completed in the early 1960s. In terms of the unity of the classic urban structure, Florair is rather an exception, yet without the monotony of larger modernist ensembles. This circumstance, as well as the architecture, which can almost be called classic and which is very demanding for modern social housing construction, makes the buildings appear like a fascinating aberration in the urban fabric.

The owner and developer is the Société du Logement de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale (SLRB), the largest public housing company in the metropolis, together with its local department Foyer Jettois. The client was aware of the architectural qualities of the existing buildings and wanted to preserve them or adequately transfer them to the renovated state. However, the available budget only included provisions for maintenance and a limited subsidy. In order to select a total planning team of architects and engineers, the SLRB organized a competition, which Atelier Kempe Thill won in 2014 in cooperation with Canevas Architectes et Ingénieurs and the Greisch engineering office.

Craft Architecture

The two buildings Florair 2 and 3 each contain around ninety apartments. They are organized like many social housing buildings in Brussels designed at the time: around two staircase cores per building, which come together in a common entrance hall. Each stair core gives access to four apartments per floor, oriented on one side respectively with expansive panoramic glazing. Inside the apartments, the rooms are accessed via a corridor that also connects bathrooms, toilets, and storage rooms.

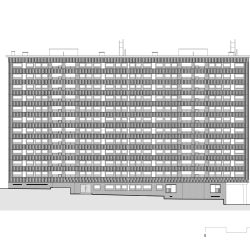

The construction consists of a skeleton of in-situ concrete supports, beams, and ceilings. This skeleton is filled with masonry parapets on which the windows are mounted. The balconies are also bordered with brick parapets. The outside skin for the masonry comprises prefabricated concrete elements, each of which is anchored by two steel reinforcements in the masonry bond of the parapets. In contrast to the more industrialized modernism of the 1960s and 1970s, from a technical point of view the Florair project is primarily a handcrafted building with some industrial components.

The architecture is designed in the optimistic spirit of the 1950s: spacious, naturally composed horizontal façades with elegant steel-frame windows, prefabricated concrete parts, partly colored tiles, a base floor made of Belgian bluestone, and a symmetrically composed entrance, each with a spacious canopy reminiscent of American hotels of this period. Even works of art are integrated on the ground floor. Moreover, all four buildings differ in a subtle way, both in their façade structure with various projections and recesses, semi-loggia-like balconies, et cetera, and in their materials and colors.

After more than sixty years, the buildings were in need of renovation. Some of the concrete elements had fallen off, creating dangerous situations. In terms of energy and acoustics, the buildings were completely unacceptable due to the uninsulated parapets, but above all due to the steel-frame windows with single panes.

External Insulation versus Existing Qualities

The refurbishment requested by the client was initially based on an energetic upgrade of the uninsulated façades. The single-glazed windows were to be replaced with new double-glazed windows. In addition, all freshwater and wastewater pipes, the ventilation, the bathrooms, and some of the kitchens had to be renewed. All of this needed to be done in a largely occupied state, since it was impossible for the housing association to empty the apartments and relocate such a large number of tenants.

The starting point for thermal insulation was external insulation, since internal insulation was not feasible due to the unmanageable thermal bridges and the need to keep construction work in the apartments to an absolute minimum.

In order to define the strategy for the renovation project, a thorough study of the qualities of the existing building was first necessary. The materialization of the existing complex initially gave the overall ensemble a monolithic appearance. However, the use of different materials emphasizes certain elements, in particular the balconies, the entrances, and the works of art, thus varying the unity without contradicting it. The sophisticated treatment of the concrete, stone, and ceramic cladding creates a subtle second reading of the building. All these qualities were completely called into question by the necessary external insulation.

Parapet Bands

Due to the circumstances described, the starting point for the concept was a reinterpretation of the existing architecture through a new building shell, a kind of translation of the existing qualities into a new form that was strongly based on the old one. The handling of the windows, and the closed parts of the façade between the windows, was decisive.

Technically, there was the problem that the masonry parapets were of poor quality for today’s structural standards. They were not bonded enough to support the much heavier new windows, the dynamic loads from opening and closing the windows, and the wind pressure. There are even doubts as to whether the insulation and even light façade cladding could be attached to the parapets. This meant that the new windows and new façade cladding could not be mounted on the parapets but instead had to be attached directly to the concrete supports and panels of the vertical supporting structure with an auxiliary construction.

For these reasons, it was initially suggested that the horizontal parapet bands between the windows should be made of prefabricated concrete parts, which would stretch like beams between the supporting columns and serve to support the windows and protect them from the weather. When this solution proved to be too expensive after an initial tender, the client decided to carry out the project in a somewhat more cost-effective variant with corrugated iron cladding. However, in order to be able to attach the corrugated iron and, above all, the new windows, a steel construction needed to take over the span between the supporting columns. The effect is a modernist tightening of the existing architecture: the horizontality of the façade bands is significantly strengthened by the simplification of the façade. The classic structure with the projecting edge of the roof and the deliberate distinction between the base and the basement also reinforce this effect. Florair 3 was given a gray-bronze color scheme, Florair 2 a dark bronze one.

Coarsening of the Windows and Mosaic Tiles

The windows are the second element that decisively determines the architecture. The elegant steel frames of the existing windows were only filled with single glazing. The new windows require heavy double glazing, which necessitates profiles that are four to five times as wide. For this reason, the divisions of the windows were greatly reduced in order to ensure a harmonious relationship between glass surfaces and profiles. Paradoxically, the façade had to be greatly simplified in order to achieve a certain elegance.

The windowsills are now more accentuated than was originally the case thanks to the new edged framing elements in sheet metal. This measure serves to introduce a both technical and architectural mediating element. Technically, a strategy to absorb the construction tolerances is essential because of the many jutties and setoffs within the façade geometry. Architecturally, the windowsills make the openings appear slightly larger, giving the building a little more visual openness and spaciousness.

The ground floor base in Belgian bluestone is also insulated. In order to translate the character into a comparable form, a system of insulation with glued mosaic tiles was used. With Florair 2 they are dark brown, with Florair 3 medium brown. The bluestone was preserved on the floors in the central entrance area.

The existing artwork in Florair 3 was integrated into the new appearance. It was left out of the insulation and given a glazed display case with indirect lighting.

Sustainability through Destruction

The confrontation of the high-quality existing architecture with the unavoidable external insulation shows the fundamental dilemma of the project: as an architect, in the case of an architecturally strong existing project, it is actually most convincing to take a more reserved and respectful attitude toward the buildings. Due to the unavoidable external insulation, the task ultimately entailed the destruction of the existing architecture. Original sculpturality, ornamentation, and thin window profiles were untenable under the circumstances. A new architecture had to be created in front of the insulation, so to speak, which translates the spirit of the historic building into a new design and thus the spirit of modernity into the twenty-first century. The classic structure and horizontality, the subtle sculptural nature of the façade through various small projections and recesses, and the panoramic windows had to be created in a new way.

The massive stone architecture was replaced by a layered structure and an outside skin made of sheet metal just 0.75 millimeters thick. After sixty years of intensive use, it would have needed just a little more budget to be able to materialize the project even more solidly again. However, the project has been energetically optimized for the housing association and residents, which has a very positive effect on life in the houses.

_

Insulated Modernity

FOYER JETTOIS

FLORAIR 2 & 3

BRUSSELS BELGIUM

Facts urban plan:

program: 2 residential buildings, social housing

renovation façades and roof, conformities (MEP, fire safety)

architects: Atelier Kempe Thill (Rotterdam, NL)

in collaboration with Canevas architecture et ingénierie (Liege, BE)

engineering consultants: Bureau d’études Greisch (Liege, BE)

Facts buildings:

program: Florair 2 – 91 apartments

Florair 3 – 90 apartments

Shared communal spaces

address: Florair 2

avenue Guillaume de Greef 200/299

1090 Brussels

Florair 3

avenue Guillaume de Greef 300/399

1090 Brussels

architects: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners

Canevas architecture et ingénierie

client: SLRB-BGHM

Lojega

Planning:

competition: 2014

start commission: 2014

start execution: April 2019

date delivery: September 2022

Building:

building size: Florair 2 & 3: 17130 m2

Florair 2 8550 m2 Florair 3 8580 m2

Costs (excl. tax):

accepted tendering offer (2018): 9.618515,33 €

lot 1. exterior 6.113384,77 €

facade renovation, exterior layout

lot 2. interior, installations 3.505125,00 €

MEP conformities, fire safety conformities,

bathroom renovations

final building cost (2022) 12.106244,26 €

lot 1. exterior 7.302753,14 €

facade renovation, exterior layout

lot 2. interior, installations 4.803491,12 €

MEP conformities, fire safety conformities,

bathroom renovations

Design team project:

Team competition: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners, Rotterdam NL

André Kempe, Oliver Thill with

Pauline Durand, Louis Lacorde, Eldrich Piqué, Martins Duselis

in collaboration with:

Canevas architecture et ingénierie, Angleur BE

Anne Dengis, Hélène van Sull

Team project: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners, Rotterdam NL

André Kempe, Oliver Thill with

Kim van Kempen, Marc van Bemmel, Pierre Berthelomeau, Pauline Durand, Louis Lacorde, Christophe Banderier,

Eldrich Piqué, Kento Tanabe, Martins Duselis

in collaboration with:

Canevas architecture et ingénierie, Angleur BE

Anne Dengis, Laurianne Hoet, Hélène van Sull,

Alain Hinant

Team construction: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners, Rotterdam NL

André Kempe, Oliver Thill with

Reinier Suurenbroek, Jeronimo Mejia, Kim van Kempen,

Kento Tanabe

in collaboration with:

Canevas architecture et ingénierie, Angleur BE

Jan De Four, Laurianne Hoet, Alain Hinant

photographer/

copyright: Architektur-Fotografie Ulrich Schwarz