Lagula Arquitectes . photos: © Del Río Banni

The client of this house is a helicopter pilot. “I like everything that flies. If I were alone, I would live in a hangar”, he confesses in the first meeting. But he has a family and there is a need for a somewhat more domestic roof over his head. However, the house is his personal project and he wants the construction to be emotionally intense, like the sensation of flying.

Large commercial aircraft try to minimize this emotion, avoiding turbulence, sudden movements… Flying, that what flying really means, is not made for everyone. It is an uneasy, unstable, risky situation. And in a small aircraft this sensation is magnified: freedom and lightness, at the same time as the evidence of the inescapable gravity, the wind, the thermal currents, and the possibility of falling at any moment. Living on a limit, the very border between floating in the air or crashing into the ground.

The house thus arises from the search for the emotion of this unstable position, enhanced by the impression of the emptiness underfoot or the cathedral-like architectures among the cloud formations. Amazing spaces, paradigms of the sublime defined by E. Burke and I. Kant in the 18th century, when the first hot-air balloon flights were made, and when its first crew members perished.

Burke said: “The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror”. And Kant continued: “The sublime must always be large, the beautiful can also be small. The sublime must be simple, the beautiful can be decorated and ornamented. A great height is just as sublime as a great depth, but the latter is accompanied with the sensation of shuddering, the former with that of admiration; hence the latter sentiment can be terrifyingly sublime and the former noble”.

This sensation of amazement in front of great architectures, as well as before the works of nature, is what the house pursues in its interior spaces. From the first sketches, large volumes are proposed, the highest allowed by the regulations: double spaces in the most representative areas of the dining room and living room, or a triple height in the lobby that starts in the basement, at the foot of the vehicle ramp, and reaching almost ten meters.

A concrete shell envelops these voids, creating these spaces. Perhaps intuiting the proportional relationship between the heaviness of the material and the impression that its flight will produce, this is the client’s second request: “I want the house to be entirely made of concrete”. As in a Gothic cathedral or the unprecedented take-off of an Airbus 380, experiencing the lightness of something heavier than air reinforces the sublimity of the stony envelope that defines the house.

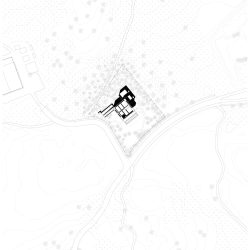

This rotundity makes the construction a landmark in the landscape of the Camiral Resort in Caldes de Malavella, near Girona, where the house is located. Its presence is inevitable, it causes astonishment and curiosity. Is it a house or a golf facility? The client is convinced and gives it a very airport-like name: Terminal 1.

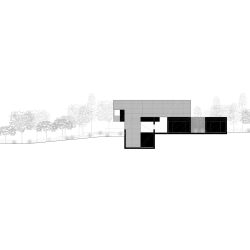

Terminal 1 is located at the top of a double plot, central within the resort complex. Behind it, the original oak forest is preserved. In front, a large garden has visual continuity towards the holes of the Tour Course. The house presides over the site and overlooks the 16th hole but, at the same time, it is viewed from the Driving Range, to the west, in slightly higher grounds. Despite its artificial condition, or perhaps because of it, it stands naturally among the grey cork oaks. In the misty winter mornings it has something of a cromlech, a megalithic table, a primitive monument.

The concrete envelope defines a maximum perimeter for the box and provides it with direction by opening with large overhangs to the north and south sides, while resting on massive legs to west and east. To the west, totally opaque walls protect the house from unwanted views and from being hit by the occasional ball arriving from the Driving Range. The cutouts in the shell to the north and south lift the skin off the ground and create porches and terraces to allow views and permeability to the interior.

The main access is on the north side, along a double ramp defined as a 06-24 runway, according to the client’s aeronautical terminology: 06L, descending, leads to the basement and the unloading area; 06R, ascending, proposes a promenade through a bridge to the entrance porch, under the concrete shell. The approach, open but under cover, predisposes the visitor by means of expressive zenithal light entrances at a great height.

The interior of the house reinforces the infrastructural character of the building. Space, the leading actor, rises before the visitor, inviting him to raise his head, almost looking for boarding gates displays. Then, like heavy architectures defying gravity, abstract black volumes appear hanging in that void. These cuboids enclose spaces inside, while define others between their borders and the perimeter concrete shell. Like in aviation, these black boxes jealously guard the records of the most private lives of their occupants: bedrooms with en-suite bathrooms in olive green glazed ceramic for the children and the couple, or a second, more secluded living room from which the original forest can be contemplated.

Around it, under the boxes, the rest of the program is organized between American walnut wood cladding and furniture: the kitchen open to the dining room and living room, the accesses to the bedrooms and the stairs to the second floor or basement, where two more bedrooms, bathrooms and a multipurpose space with an office are located. Homogeneous materials qualify the spaces with their expressiveness: the orderly grid of the concrete formwork, smooth walls bathed by the grazing light of the skylights, the lightly polished concrete floors, the continuous coatings of the black boxes in interior and exterior continuity, or the warmth of wood and glazed ceramics. These are magnificent yet friendly and stimulating spaces.

The defiant lightness of these floating black boxes, reinforced by their rotundity and simplicity in shapes and materials, make explicit the disconcerting and apparently unstable balance of the whole. This impression of suspense before heavy floating architectures is also felt in the pilot’s stomach when, being at the controls, he finds himself hanging over the abyss.

And yet, to some extent, this is a limited hazard: loaded with procedures and routines to maintain safety, flying is an orderly risk. So is the house. The very act of building implies the definition of a logic, of a structural and constructive hierarchy of elements connected for the creation of the whole: the shell, suspended on the fronts and overhanging the black boxes, is supported by large beams of almost twenty meters, visible above the roof; beams that unload the weight of the whole house through screens on both sides of the shell, to the foundations and, through concrete wells, to the resistant ground.

On their side, built in sections, the shell is literally a puzzle for the builders: double walls of eighteen-centimetre reinforced concrete, with ten centimetres of PIR insulation inside. Forty-five centimetres of total thickness of walls formed in straight and angled segments to achieve continuity at the corners so the box effectively expresses. Orderly formwork stripping processes to allow the beams to be loaded following a hierarchical logic of their load transmission…

Concrete allows for such structural and constructive audacity. And while it is undeniable that cement manufacturing carries a significant environmental burden, with significant carbon dioxide emissions, concrete has been central to the development of modern architecture. Material strength not only ensures structural stability over time, but also minimizes the need for frequent replacement, thus reducing the resource and energy demands associated with repeated rebuilding.

On our path toward a more sustainable future, it is crucial to embrace innovation in cement manufacturing. Research and development in cleaner production techniques, the use of recycled materials, and the incorporation of more efficient processes to reduce the environmental footprint associated with reinforced concrete, but without giving up such a versatile and resilient material, and the poetics that, as in Terminal 1, underpin it.

_

Architects: Lagula Arquitectes

Client: Bob Haugh

Collaborators: Ordeic (Engineering), Gespromat (Quantity Surveyor), Natàlia Mitjà (Landscaping), Camila Acosta (Interior Design)

Project management: PGA Golf de Caldas

Builder; Busquets Residencial

Location: Camiral Resort, Caldes de Malavella (Girona)

Built area: 890 m2

Year of construction: 2023

Photography: Del Río Banni

El cliente de esta casa es piloto de helicóptero. “Me gusta todo lo que vuela. Si estuviera solo, viviría en un hangar”, nos confiesa en la primera reunión. Pero tiene familia y la necesidad de un techo algo más doméstico se impone. Con todo, la casa es su proyecto personal y quiere que la construcción sea emocionalmente intensa, como la sensación de volar. Las grandes aeronaves comerciales intentan minimizar esta emoción, evitando turbulencias, movimientos bruscos... Volar, lo que es volar, no está hecho para todo el mundo. Es una situación inquieta, inestable, arriesgada. Y en una pequeña aeronave esa sensación se magnifica: libertad y ligereza, al mismo tiempo que la evidencia de la ineludible gravedad, del viento, de las corrientes térmicas, de la posibilidad de caer en cualquier momento. Vivir en un límite, la frontera entre flotar en el aire o estrellarse. La casa surge pues de la búsqueda de la emoción de esa posición inestable, aumentada por la impresión del vacío bajo los pies o de las arquitecturas catedralicias entre las formaciones de nubes. Espacios asombrosos, paradigmas del sublime definido por E.Burke e I.Kant en el s. XVIII, cuando se realizaron los vuelos iniciales en globo aerostático, y en el mismo momento en que perecieron sus primeros tripulantes. Decía Burke: “La pasión causada por lo grande y lo sublime en la naturaleza, cuando aquellas causas operan más poderosamente, es el asombro, y el asombro es aquel estado del alma en el que todos su movimientos se suspenden con cierto grado de horror”. Y seguía Kant: “Lo sublime ha de ser siempre grande: lo bello puede ser también pequeño. Lo sublime ha de ser sencillo; lo bello puede estar engalanado. Una gran altura es tan sublime como una profundidad; pero a esta acompaña una sensación de estremecimiento, y a aquella una de asombro; la primera sensación es sublime, terrorífica, y la segunda noble”. Esta sensación de asombro frente a las grandes arquitecturas, al igual que ante las obras de la naturaleza, es la que persigue la casa en sus vacíos interiores. Desde los primeros esbozos se plantean grandes volúmenes, al límite de la altura reguladora: dobles espacios en las zonas más representativas del comedor y el estar, o una triple altura en el vestíbulo que nace en la planta sótano, al pie de la rampa de vehículos, y que casi alcanza los diez metros. Una cáscara de hormigón envuelve esos vacíos, crea esos espacios. Quizás intuyendo la proporcional relación entre la pesadez del material y la impresión que producirá su vuelo, ese es el segundo requerimiento del cliente: “Quiero que la casa sea por entero de hormigón”. Pues como en una catedral gótica o el inaudito despegue de grandes aeronaves como el Airbus 380, experimentar la levedad de lo más pesado que el aire, refuerza la sublimidad de la mineral envolvente que define la casa. Esta rotundidad hace de la construcción un hito en el paisaje del Camiral Resort en Caldes de Malavella, cerca de Girona, donde se ubica. Su presencia es inevitable, causa asombro y curiosidad. ¿Es una casa o un equipamiento del golf? El cliente lo tiene claro y le otorga una denominación muy aeroportuaria: Terminal 1. Terminal 1 se sitúa en la parte alta de una parcela doble, central dentro del conjunto del resort. A su espalda se mantiene el bosque de encinas original, frente a ella se abre un gran jardín con continuidad visual hacia los agujeros del Tour Course. La casa preside el solar y mira al agujero 16 pero, a la vez, es mirada desde el Driving Range, al oeste, algo más elevado. Pese a su condición artificial, o quizá por ella, se implanta con naturalidad entre los grises alcornoques. Entre la niebla en las mañanas hibernales tiene algo de crómlech, de mesa megalítica, de monumento primitivo. La envolvente de hormigón define un perímetro máximo para la caja y le confiere dirección abriéndose con grandes voladizos hacia los lados norte y sur, mientras descansa sobre macizas patas a este y oeste. Hacia poniente muros totalmente opacos protegen la casa de las vistas no deseadas del campo de prácticas, y de alguna eventual pelota lanzada con demasiado ímpetu. Los recortes de la cáscara a norte y sur levantan esa piel del suelo y generan porches y terrazas para permitir la visión y la permeabilidad hacia el interior. El acceso principal, se produce en el lado norte, a lo largo de una doble rampa definida como pista de aterrizaje dirección 06-24, según la terminología aeronáutica del cliente: la 06L, descendente, conduce al sótano y la zona de descochado; la 06R, ascendente, propone una promenade a través de un puente hasta el porche de entrada, bajo la cáscara de hormigón. La aproximación, abierta pero a cubierto, predispone al visitante mediante expresivas entradas de luz cenital a gran altura. El interior de la casa insiste en el carácter infraestructural del edificio. El espacio, protagonista, se eleva ante el visitante, le obliga a levantar la cabeza, casi buscando indicaciones hacia las puertas de embarque. Entonces, como pesadas arquitecturas desafiando la gravedad, unos abstractos volúmenes negros aparecen colgando en ese vacío. Ortoedros que encierran espacios en su interior, a la vez que limitan otros entre su perímetro y la cáscara de hormigón. Como en la aviación, estas cajas negras guardan celosamente los registros de la vida más privada de sus ocupantes: dormitorios con baño en-suite de cerámica esmaltada verde oliva para los hijos y la pareja, o una segunda sala de estar más recogida que contempla el bosque original. A su alrededor, bajo las cajas, se organiza el resto del programa entre revestimientos y muebles de madera de nogal americano: la cocina abierta al comedor y estar, los accesos a las habitaciones y las escaleras de acceso a planta primera o sótano, donde se disponen dos habitaciones más con su baño y un espacio polivalente con un office. Los materiales cualifican los espacios con su expresividad: la retícula ordenada de los encofrados de hormigón, muros tersos bañados por la luz rasante de los lucernarios, los suelos de hormigón ligeramente pulido, los revestimientos continuos de las cajas negras en continuidad interior y exterior, o la calidez de la madera y la cerámica esmaltada. Espacios grandiosos pero amables y estimulantes. La desafiante ligereza de esas cajas negras flotantes, reforzada por su rotundidad y simplicidad en formas y materiales, explicitan el desconcertante equilibrio aparentemente inestable del conjunto. Esa impresión de suspense ante pesadas arquitecturas flotantes, es la que siente también el piloto en el estómago cuando, estando a los mandos, se encuentra colgando sobre el abismo. Y a pesar de todo se trata, hasta cierto punto, de un peligro limitado: cargado de procedimientos y rutinas para mantener la seguridad, volar es un riesgo ordenado. La casa también. El hecho mismo de construir, implica la definición de una lógica, de una jerarquía estructural y constructiva de elementos conectados para la creación del todo. Así, el caparazón de hormigón, suspendido en los frentes y descolgando las cajas negras, se sostiene mediante grandes jácenas de casi veinte metros, visibles por encima de la cubierta; vigas que descargan el peso de toda la casa a través de pantallas a lado y lado de la envolvente, hacia los cimientos y, mediante pozos, hasta el terreno resistente. Por su lado, construidos por tramos, los muros de la cáscara son literalmente un rompecabezas para sus constructores: hojas dobles de hormigón armado de dieciocho centímetros, con diez centímetros de aislamiento PIR en su interior. Cuarenta y cinco centímetros de espesor total de muros encofrados en segmentos rectos y en ángulo para conseguir una continuidad en las esquinas, fundamental para obtener el efecto caja aristada del volumen. Procesos de desencofrado ordenados para permitir una puesta en carga de las vigas siguiendo la lógica de su jerarquía en la transmisión de cargas… El hormigón permite esa audacia estructural y constructiva. Y aunque es innegable que la fabricación de cemento conlleva una importante carga ambiental, con emisiones significativas de dióxido de carbono, el hormigón ha sido fundamental en el desarrollo de la arquitectura moderna. La resistencia del material no solo asegura la estabilidad estructural a lo largo del tiempo, sino que también minimiza la necesidad de reemplazo frecuente, reduciendo así la demanda de recursos y energía asociada a una reconstrucción reiterada. En nuestro camino hacia un futuro más sostenible, es crucial abrazar la innovación en la fabricación de cemento. Investigaciones y desarrollos en técnicas de producción más limpias, el uso de materiales reciclados y la incorporación de procesos más eficientes para reducir la huella ambiental asociada con el hormigón armado, pero sin renunciar a un material tan versátil y resistente, y las poéticas que, como en Terminal 1, en él se sustentan.