The environs of Andeer are beautiful: mountains, rivers, meadows, and forests. So is the well-preserved village. As if time had stood still. Quiet and peaceful, if it weren’t for the A13, the motorway that connects the village with Chur to the north and, via the San Bernardino, to the canton of Ticino and Italy to the south.

And this is supposed to be location of a chapel? Statistics show that motorway chapels enjoy great popularity, but it is still surprising that the community of Andeer has decided to build one here in this landscape. There are already several chapels in the surroundings, and indeed throughout all of the Grisons. They were built centuries ago and lie embedded in this exquisite landscape. Many of them are architectural and art historical gems, from simple plastered walls to frescoes, painted ceilings, and wood carvings. They are places that encourage people to pray and worship – or simply to stop and rest and marvel for a moment. We are familiar with many of these chapels. We have always admired this architecture for its enduring ability to fascinate people, even more so perhaps because the churches are not embedded in an urban context but are a fully functional part of their natural surroundings. It is actually our love of these chapels that made us realize we couldn’t use them as an analogous model for today’s contemporary architecture. It is impossible to conjure the aura of old walls without resorting to kitsch.

So there was nothing anywhere in the world that we might have studied and used as a source of inspiration: no typological models, no churches, no prayer room, no recent architecture. The idea for the chapel in Andeer had to emerge from the site alone, from the location, from the road. And we did not want to work with explicit religious signs or symbols, even less with Christian symbols such as a cross or representations of Christ. We were looking for architecture that would sharpen the perception of visitors—of the location, the natural environs, and even of the way they see themselves.

The project is also unusual for us because neither the spatial program nor the location were clearly defined. These questions and, of course, the development of the architectural concept acquired shape in the course of several meetings and fruitful, candid conversations with representatives of the community and the pastor of Andeer.

Initially, there were specific questions to deal with: where should the motorway chapel be built? Not just anywhere in the landscape but alongside a motorway. As close as possible. At one point we even thought of building it above the motorway. Then we discovered that there was already a bridge across the road connecting the village and the landscape. We made countless designs, including a covered bridge, like a little basilica above the road. A possibility that we had to abandon because it was too costly, but we did like the idea of a bridge that connects. A path to a place, in fact, a path as place… or even right through the chapel? But how would a space like that work?

Because of the location next to a motorway, we knew we would have to deal with the noise. Literally. The noise of the street that we wanted to overcome and leave behind on entering the chapel. Not just a single door separating inside and outside acoustically and spatially but a sequence of spaces, of different and distinct chambers—like the human ear. Acoustic waves enter the auditory canal, penetrating deeper and deeper, via various stations, until our brain converts them into sounds that we perceive and identify as such.

We explored a sequence of that kind in developing our design. But we avoided an anthropomorphic analogy because the first organically inspired sketches and models did not convince us. We wanted to find something else, something more archaic. Something that would instantly target human perception: the altered perception of sounds and sights.

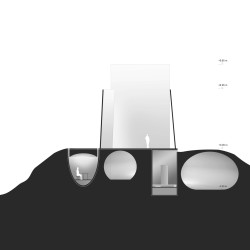

We started out with a shape as abstract as possible, a kind of placeholder, a solid white cube, with a variety of zones defining its complex inner life. Very introverted. The deeper you go, the weaker the sounds from the motorway and the stronger the sound of your own footsteps. Finally, when you reach the last room, strong daylight streams into the heart of the chapel and you see a panoramic view of the landscape, the village, and the lush green meadows and woods. Perception of the vegetation is heightened by the complementary red of a room-height pane of tinted glass. The sun, setting in the evening, shines through the red glass into this last portion of the chapel, which leads directly to the landscape outside.

We wanted the architecture to reinforce perception. Just like this last section, we wanted each part of the chapel to have a specific quality, a focus of its own. Ordinary, even trivial things: for example, a view of the sky, concentration while reading, or the perception of sounds, external and internal, like our footsteps or our breathing. We realized that the closed cube could not meet the specifications. It was too hermetic and too architectural. We had to start hunting again. We wanted to create space but not a closed architectural volume. It should be more like a path coming from outside, passing through a sequence of specific rooms, and then leading directly outdoors again. But we did not really perceive this as a path until we laid it through the earth, like a passage through an organism or cave. We realized that we now had the potential of not just one but many analogies and associations, which is what we had wanted to achieve from the very start. The last room with the red pane of glass opens up into a cave-like oval, reminiscent of the early Christian or heathen sites that archaeologists have discovered in the neighboring community of Zillis. Along the funnel-shaped earth space, visitors find two other small chapels: the first for readers, with even daylight coming into the round room from above and the second with a candle, a matte, reflecting wall, and a single skylight. This is the most personal place for visitors; here they are confronted with themselves.

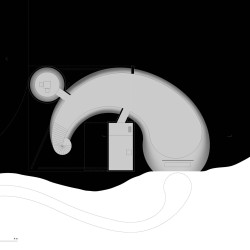

In short, the earth room is conceived as a sequence of chapels with a ground-level exit facing west as well as access from above, down a broad, snail-shaped flight of stairs. The latter is like a hole in the ground or like a drain, or maybe even like the round opening of a dome. We did not want to define it but we did want to enclose or surround it, like a garden or courtyard. That meant four walls of equal height and at right angles, but not as part of the fixed walls of a room: that would have been too much like a building again. The walls just lean against each other; they lean and support at the same time. One of them stands upright. Almost like the wall of a choir. A simple gesture that emerged almost in play.

Herzog & de Meuron, 2020

–

Herzog & de Meuron Team:

Partners: Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Andreas Fries (Partner in Charge)

Project team: Martin Knüsel (Associate, Project Director), Daniel Wilson (Project Manager), Carla Ferrando, Monica Gaspar Bonilla, Jonas Läufer, Anna Ludwig

Client:

IG Autobahnkirche A13

Planning:

Cost Consulting: Christen Baukosten- und Projektmanagement, Basel, Switzerland

Structural Engineering: Conzett Bronzini Partner AG, Chur, Switzerland

Specialist / Consulting:

Traffic Consulting: Casutt Wyrsch Zwicky AG, Falera, Switzerland

Visualizations: Aron Lorincz Ateliers, Gödöllő, Hungary

Building Data:

Gross Floor Area (GFA): 280 sqm

GFA above ground: 130 sqm

GFA below ground: 150 sqm

Number of Levels: 2

Height: 10 m

_