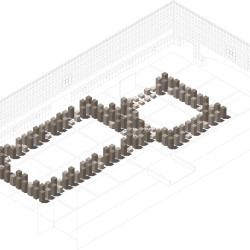

In the beginning of the 1980’s, architect and theorist Peter Eisenman coined the concept of “Cities of Artificial Excavation” in the context of a design competition for the 1987 IBA (Internationale Bauausstellung Berlin). The concept that would in fact characterize the work of the American architect between 1978 and 1988 was both a response to the superficial recovery of history by postmodernism and an operative device for radical design. In a way, it proposed a framework for assertively acknowledging the condition of the end of history, assuming its fictional dimension. “Artificial excavation” was the ability to invent an archaeology as a kind of abstract memorial density achieved by a reversed process. This comes to mind when considering the public installation completed by the Portuguese office Promontorio at the Belem Cultural Centre, in Lisbon. The programme A Square in Summer has been implemented by architect and curator in residence André Tavares of the Centre’s architecture space, Garagem Sul, as a way to activate public interest for this cultural institution with ephemeral interventions by architects. This year’s installation “Open-Sky Architecture” by Promontorio, is made up of a double colonnade structure that defines two smaller courtyards within the Centre’s main square. The installation is singlehandedly devised in piled-up blocks of recycled cork agglomerate, as per the sponsor’s pre-condition, and comprises a relatively open programme consisting of an open-air auditorium for the screening of a film cycle during Lisbon’s hot summer evenings. Under such tight material and budget constraints, Promontorio’s project is tremendously sharp and intentional.

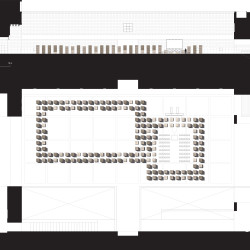

The structure is based on a single free-standing element, the column, which, in its systematic replication, defines squares and galleries, evocative of primordial building typologies. An idealised aura of ruined architecture is brought about by the absence of a roof and the different heights of the columns; an incomplete architecture that reminds us of waning archaeological sites. And it is precisely here that the “artificial excavation” of Eisenman comes to minds. History is staged here as a powerful reminiscence for a new architecture. But in fact, this anachronistic ruin emerges out of the main square of the building completed in 1992 by architects Vittorio Gregotti and Manuel Salgado. In his seminal book “The Architecture of the City”, Aldo Rossi shows us how a building structure evolves in time; longwinded metamorphic processes that eventually leave traces in the physical form of a building. Unlike the gradual processes that characterize the evolution of the urban artefacts, in Promontorio’s installation, time is somehow reversed, as the ruin appears after the building to which it owes its foundations. In this new structure, columns are laid obsessively following the grid of the very geometric pattern of the host building and the stereotomics that structure the Centre’s main square. Significantly, the modular cork blocks, sized 1.00 x 0.50 metres, are paired in 1.00 x 1.00 metres’ base, with an intercolumnium of the same length, making a constant rhythm of solid and void. The effect is an accentuation of the all-embracing metrics laid by the Italian and Portuguese architects.

The new structure definitely belongs to the site. Nonetheless, this “excavation” by Promontorio seems more evocative of Rossi than Eisenman. In fact, let us recall here the prolific dialogue established by the two architects from the 1970s onwards. Rossi, who was a usual presence in the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, in New York, led by Eisenman, expanded the institute’s international influence, while Eisenman, in 1982, would write the polemic introduction of the English edition of “The Architecture of the City”. But apart from these affinities, their theorical agenda was decisively divergent, as the installation of Promontorio somehow actualizes. Insofar as the ambiguity of this new ruin is the design concept per se, the proposal distances itself from the neutralization of history intended by Eisenman. In fact, it is not the experience of the abstraction of memory that Promontorio seeks, but the resonance with the history of architecture. And it is here that Promontorio pays its dues to Rossi. Historical artefacts are the result of formal developments that unfold over time, maintaining their essential typological character. It is through the lens of typological research and Rossi’s idea of “I’architettura analoga”, that the Open-Sky Architecture is best understood. Without any explicit historical reference, the abstracted structure of Promontorio resonates with timeless building types, from the agora to the cloister. The enclosures defined by the columns creates spaces that, at a public scale, are both intimate and archaic. Colonnades define paths to circulate and the places to stay, allowing for the experience of nearness and openness and the unavoidable game of hide-and-seek. On the other hand, the installation, geometrically grounded in the matrix of the Cultural Centre, changes and redefines our relation with its main square. The columns structure is organized in accordance with the flow of the Centre’s users, opening towards the entrance of the Berardo Collection and allowing a peripheral circulation without penetrating the installation. This said, it would be hard not to cave to the appeal of crossing it and discover the secrets of this “pure architecture”. The public reaction to this installation is impressive, with people actively exploring it in a number of ways; strolling, hiding, sitting or observing. This enigmatic structure induces curiosity and demands a creative attitude from users.

Yet another level is relevant here; one that acknowledges Kenneth Frampton as an important reference in the work of Promontorio. Awkwardly, we should mention that Frampton was another of the key figures of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. The materiality of the installation poses an irreconcilable ambiguity, with cork, a lightweight material, being used in reference to stone, which is a heavy one. In fact, the building in itself also suggests a similar tectonic ambivalence, with its rusticated stone applied has a skin. The columns, built in blocks of the same width and length, but significantly different heights and nonetheless consistently applied with the same rule of assembly, give the structure a powerful tectonic articulation. The odd resemblance of texture between the Centre’s rusticated stone and the cork construes an analogy that favours the intentions of Promontorio. A sense of uncanniness looms across the whole.

We are invited to witness different layers of ambiguity in this Open-Sky Architecture. To note; the anachronistic nature of the ruin metaphor; the tension between reference models of permanence and the ephemeral character of the installation; the abstract character of the structure, historically rooted on the idea of typology; the usefulness of the programme and intensity of the experience it provides; and, last but not least, the odd tectonic transferences of its materiality. In times of increasingly technocratic design, Promontorio offers the public a piece of architecture to be both freely appropriated and reflected upon. In its apparently discreet aim, Open-Sky Architecture challenges us to take a moment to experience architecture and reflect on its contempoarary condition.

The Square of Analogical Excavation

Text by Luís Santiago Baptista

_