Studio MK27 – Marcio Kogan + Suzana Glogowski . photos: © FG+SG architectural photography . + archdaily

Density or looseness? Intensity or laid-backness? Public or private? Urban or suburban? The problem in creating new housing on the edge of the city is to somehow synthesise all of these seeming opposites – not to choose between them but to lift a little from them all to create a new cocktail of the familiar and the foreign, the everyday and the exotic.

_

MK27’s designs for Somosaguas, a new development at the expanding edge of Madrid, is the Brazilian studio’s first foray into European housing. The intention was to create a kind of habitat, a new neighbourhood in which the houses are loosely arranged around a web of public spaces – streets, plazas, parks, a pool – and in which the communal streetscape occupies as much area as the dwellings themselves. It is a design for a public kind of living – a nod to the Spanish proclivity for living in the city and occupying the spaces of urbanity arguably more than they do their own homes (which remain as places for sleeping and siestas).

The houses themselves blend typologies in the same way as does the development itself. There is a deliberate but delicate touch of the pueblo about their arrangement – the white walls and the cubic blocks. There is a little of the Bauhaus Siedlung – the model village established as an experiment in contemporary living and construction – the restrained, minimal palette and aesthetic and the functions s a trailer for how a modernist life might look. There is a little of the languorous Brazilian architecture of luxurious relaxation blended with, frankly, a hint of the holiday village, a sense of a place apart and of retreat.

In the complexity of its composition, the layering of the landscape and the weaving of a web of public outdoor space, an architecture emerges. The houses are elongated – attenuated so that their walls begin to define emergent streets rather than the staccato landscape of individual cubes. Yet a series of interventions, repeating motifs and urban and landscape devices appears to stop the spaces between the houses becoming alleys and to break down too much regularity. Kinks, setbacks, steps, terraces and greenery create a variety of sub-urban spaces and a coherent internal language which could in theory, be expanded and replicated, which is exactly what the architects intended, creating the development as a kind of prototype for a roll-out programme, a model which becomes more efficient and more practical as experience of building and dwelling grows.

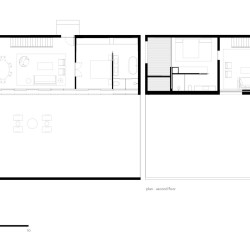

Equally important is the separation of traffic from pedestrians. This might look like a development of two storey houses but it is in fact based on a three storey cross-section with an entire subterranean layer of underground parking. Each house has access to its parking space internally, individually plugged in to the parking layer which is otherwise invisible. It is a system that has the advantages of a private garage but without disfiguring the house fronts or clogging up street level with vast expanses of garage doors, driveways and traffic.

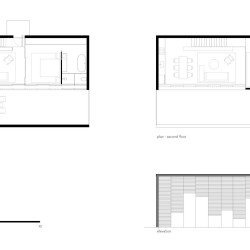

The individual houses appear quite modest in dimension, with a width of only 5.5m (each is the same width although lengths vary). Yet inside they reveal a surprising complexity of interlocking spaces and configurations of solid and void, wall and opening. The ground floors are transparent – accommodating the public functions of life and entirely glazed walls open into courtyards which mirror the interior spaces so that the broad area appears to flow into the outdoor space seamlessly. In the smaller houses, one elongated room accommodates the kitchen, dining and living functions of the house with can be subdivided or allowed to flow into one another for an impression of endless space.

In the larger versions that more public space is also extended upwards via a void which expands the surface area of the window which appears here as a double-height opening and which will eventually allow the canopy of the trees to impinge on the interior just as the floor appears to steal space from outside. A gallery above occupies the cubic volume introducing a more intimate scale to the spaces below and above and a contrast to the verticality of the window plane. Open-tread stairs and open-plan spaces make the most of the internal dimensions, leaving space uninterrupted.

The top surface of this glazed box layer becomes a terrace above, so that each horizontal, constructed plane is used to the full, each roof becoming a room. That sense of the outdoor space melding with the interior is intensified by some terraces being defined by walls with openings, like the rooftop rooms of Le Corbusier or Barragan.

On top of the transparent layer below is placed a more private and protected cube. This shelters the sleeping areas, its entirely opaque walls facing the courtyards and punched side windows emphasising the sensation of an enclosed, heavily-protected and more intimate space. The play of transparency and solidity between the ground and first floors becomes, in a way, the architectural language which determines the whole neighbourhood, a juggling of solid block and delicate, attenuated layer, indoor and outdoor room. This subtle flipping and combination of opposites creates the visual imagery and identity, the houses subtly different yet sharing the same basic vocabulary. There is no cacophony of balconies and protrusions as all terraces are subsumed within the overall volumes of the structure. There is nothing extraneous. The minimal nature of those architectural means produces a uniquely restrained sense of place and urban landscape in which all the elements have something to do, all are defined by their function rather than their style. The simplicity of the language and its internal coherence is also a device intended to build a basic vocabulary which is flexible enough to accommodate differing needs, a modular construction based on a 1.25m grid allowing multiple variations within the same architectural language. The four basic types here are not the super-luxury dimensions of villas but, ranging between 94-230 sq m, they cover the requirements for family dwellings. The houses are planned in such a way that they can be packed onto the site with surprising density. Madrid is a dense and intense city with a population of approximately 80 people per hectare. At Somosaguas, a neighbourhood which feels loose, laid-back and very green, the demographic density is a surprising 114 people per hectare.

Rather than being set far apart from one another creating a loose agglomeration of houses, they are intimately interwoven and architectural means are used to create privacy and a sense of the individual dwelling – the sheltered courtyard gardens, the walled roof terraces, the solid upper storeys and so on.

And at the centre of all this is the water. The space in which you might expect to find an urban centre, the plaza defined by church and town hall, market or topography, gives itself instead to the communal pleasures of the pool. It is, in a way, a denial of the solid core, a relinquishing of the urban heart of the Mediterranean settlement in favour of something less substantial. But it does place a certain communal activity at the heart of the scheme, a sense that each house feeds into something larger than itself rather than trying to create its own fenced-off and self-contained utopia. If one thing unsettles here it is the fences and the walls still seen so clearly in the aerial photos. The streets and spaces here flow so fluidly that to separate them from their surroundings seems harsh and counter to the spirit of the plan.

The problem with these edge-city developments is that they easily become defensive, over-private and, in shutting themselves off, they relinquish the capacity to develop into genuinely public places. Perhaps as the neighbourhood develops and expands the streets created here will begin to weave and insinuate themselves into the emerging surrounding fabric like the tendrils of a creeping plant. The unformed nature of the surroundings makes this an uncertain experiment, a kind of walled settlement waiting for the neighbourhood to catch up before it can reveal itself. Its success on how it is used and how the city grows around it. But as a seed, a mechanism to catalyse a communal and generous-spirited life, it is a fascinating and elegant prospect.