Herzog & de Meuron . + The Elbphilharmonie

In a symbolic ceremony today, Olaf Scholz, the mayor of Hamburg, in the presence of Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron and Ascan Mergenthaler, celebrates the completion of the Elbphilharmonie and the opening of the Plaza to the public. The Plaza is a spacious terrace, placed on top of the Kaispeicher, like a gigantic joint between the old and new element of the building structure. It will be open to the public from 5 November. The ceremony this week also marks the handover of the building to the City of Hamburg. The official opening of the Elbphilharmonie’s main concert hall (“Grosser Saal”) will take place on 11 and 12 January 2017.

_

Between Hanseatic Hub and HafenCity

The Elbphilharmonie on the Kaispeicher marks a location that most people in Hamburg know about but have never really noticed. It is now set to become a new centre of social, cultural and daily life for the people of Hamburg and for visitors from all over the world.

_

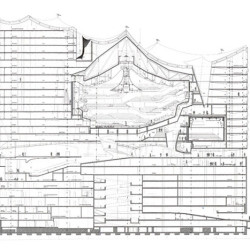

Too often a new cultural centre appears to cater to the privileged few. In order to make the new Philharmonic a genuinely public attraction, it is imperative to provide not only attractive architecture but also an attractive mix of urban uses. The building complex accommodates a philharmonic hall, a chamber music hall, restaurants, bars, a panorama terrace with views of Hamburg and the harbour, apartments, a hotel and parking facilities. These varied uses are combined in one building as they are in a city. And like a city, the two contradictory and superimposed architectures of the Kaispeicher and the Philharmonic ensure exciting, varied spatial sequences: on the one hand, the original and archaic feel of the Kaispeicher marked by its relationship to the harbour; on the other, the sumptuous, elegant world of the Philharmonic. In between, there is an expansive topography of public and private spaces, all differing in character and scale: the large terrace of the Kaispeicher, extending like a new public plaza, responds to the inwardly oriented world of the Philharmonic built above it.

The heart of the complex is the Elbphilharmonie itself. A space has emerged that foregrounds music listeners and music makers to such an extent that, together, they actually represent the architecture. The philharmonic building typology has undergone architectural reformulation that is exceptionally radical in its unprecedented emphasis on the proximity between artist and audience – almost like a football stadium.

Urban Architecture for Lovers of Culture

The new philharmonic is not just a site for music; it is a full-fledged residential and cultural complex. The concert hall, seating 2100, and the chamber music hall for 550 listeners are embedded in between luxury flats and a five-star hotel with built-in services such as restaurants, a health and fitness centre, conference facilities. Long a mute monument of the post-war era that occasionally hosted fringe events, the Kaispeicher A has now been transformed into a vibrant, international centre for music lovers, a magnet for both tourists and the business world. The Elbphilharmonie will become a landmark of the city of Hamburg and a beacon for all of Germany. It will vitalize the neighbourhood of the burgeoning HafenCity, ensuring that it is not merely a satellite of the venerable Hanseatic city but a new urban district in its own right.

_

The Archaic Kaispeicher

The Kaispeicher A, designed by Werner Kallmorgen, was constructed between 1963 and 1966 and used as a warehouse until close to the end of the last century. Originally built to bear the weight of thousands of heavy bags of cocoa beans, it now lends its solid construction to supporting the new Philharmonic. The structural potential and strength of the old building has been enlisted to bear the weight of the new mass resting on top of it.

_

Our interest in the warehouse lies not only in its unexploited structural potential but also in its architecture. The robust, almost aloof building provides a surprisingly ideal foundation for the new philharmonic hall. It seems to be part of the landscape and is not yet really part of the city, which has now finally pushed forward to this location. The harbour warehouses of the 19th century were designed to echo the vocabulary of the city’s historical façades: their windows, foundations, gables and various decorative elements are all in keeping with the architectural style of the time. Seen from the River Elbe, they were meant to blend in with the city’s skyline despite the fact that they were uninhabited storehouses that neither required nor invited the presence of light, air and sun.

But not the Kaispeicher A: it is a heavy, massive brick building like many other warehouses in the Hamburg harbour, but its archaic façades are abstract and aloof. The building’s regular grid of holes measuring 50 x 75 cm cannot be called windows; they are more structure than opening.

The New Glass Building

The new building has been extruded from the shape of the Kaispeicher; it is identical in ground plan with the brick block of the older building, above which it rises. However, at the top and bottom, the new structure takes a different tack from the quiet, plain shape of the warehouse below: the undulating sweep of the roof rises from the lower eastern end to its full height of 108 metres at the Kaispitze (the tip of the peninsula). The Elbphilharmonie is a landmark visible from afar, lending an entirely new vertical accent to the horizontal layout that characterises the city of Hamburg. There is a greater sense of space here in this new urban location, generated by the expanse of the water and the industrial scale of the seagoing vessels.

The glass façade, consisting in part of curved panels, some of them carved open, transforms the new building, perched on top of the old one, into a gigantic, iridescent crystal, whose appearance keeps changing as it catches the reflections of the sky, the water and the city.

The bottom of the superstructure also has an expressive dynamic. Along its edges, the sky can be seen from the Plaza through vault-shaped openings, creating spectacular, theatrical views of both the River Elbe and downtown Hamburg. Further inside, deep vertical openings provide ever-changing visual relations between the Plaza and the foyers on different levels.

Entrance and Plaza

The main entrance to the Kaispeicher complex lies to the east. An exceptionally long escalator leads up to the Plaza; it describes a slight curve so that it cannot be seen in full from one end to the other. It is a spatial experience in itself; it cuts straight through the entire Kaispeicher, passing a large panorama window with a balcony that affords a view of the harbour before continuing on up to the Plaza. The latter, sitting on top of the Kaispeicher and under the new building, is like a gigantic hinge between old and new. It is a new public space that offers a unique panorama. Restaurants, bars, ticket office and hotel lobby are located here, as well as access to the foyers of the new philharmonic.

The Elbphilharmonie

What kind of a space will the philharmonic be? What acoustic and architectural concerns have gone into its construction? What tradition resonates in this hall in comparison to other new locations, say, in Tokyo and Los Angeles or the ur-model in Berlin. It soon became clear that the Hamburg Philharmonic would be different from that ur-model, the Scharoun Philharmonic. The premises alone – the radical givens of the location, namely the harbour and the existing warehouse – invite change. This is a project of the 21st century that would have been inconceivable before. What has been retained is the fundamental idea of the Philharmonic as a space where orchestra and conductor are located in the midst of the audience, as it were: here the architecture and the arrangement of the tiers take their cue from the logic of the acoustic and visual perception of music, performers and audience. But that logic leads to another conclusion. The tiers are more pervasive; tiers, walls and ceiling form a spatial unity. The people, that is the combination of audience and musicians, determine the space; the space seems to consist only of people. In this respect, it resembles the typology of the football stadium that we have developed in recent years, with the goal of allowing an almost interactive proximity between audience and players. We also studied archaic forms of theatre, like Shakespeare’s Globe, with a view to exploiting the vertical dimension. The complex geometry of the hall unites organic flow with incisive, near static shape. Walking, standing, sitting, seeing, being seen, listening… all the activities and needs of people in a concert hall are explicitly expressed in the architecture of the space. This space, rising vertically almost like a tent, offers room for 2100 people to congregate for the enjoyment of making and listening to music. The towering shape of the hall defines the static structure of the entire volume of the building and is correspondingly echoed in the silhouette of the building as a whole.

Herzog & de Meuron, 2016

_

erzog & de Meuron Team:

Partner: Jacques Herzog, Pierre de Meuron, Ascan Mergenthaler (Partner in Charge), David Koch (Partner in Charge)

Project Team: Jan-Christoph Lindert (Associate, Project Manager), Nicholas Lyons (Associate, Project Architect), Stefan Goeddertz (Associate, Project Architect), Stephan Wedrich (Associate), Christian Riemenschneider (Associate), Carsten Happel (Associate), Kai Strehlke (Head Digital Technologies)

Stephan Achermann, Sabine Althaber, Christiane Anding, Thomas Arnhardt, Petra Arnold, Tobias Becker, Johannes Beinhauer, Uta Beissert, Lina Belling, Andreas Benischke, Inga Benkendorf, Christine Binswanger (Partner), Johannes Bregel, Francesco Brenta, Jehann Brunk, Julia Katrin Buse, Ignacio Cabezas, Jean-Claude Cadalbert, Sergio Cobos Álvarez, Massimo Corradi, Guillaume Delemazure, Annika Delorette, Fabian Dieterle, Annette Donat, Patrick Ehrhardt, Carmen Eichenberger, Stephanie Eickelmann, Magdalena Agata Falska, Daniel Fernandez, Hans Focketyn, Birgit Föllmer, Bernhard Forthaus, Andreas Fries, Asko Fromm, Catherine Gay Menzel, Marco Gelsomini, Ulrich Grenz, Jan Grosch, Jana Grundmann, Hendrik Gruss, Luís Guzmán Grossberger, Christian Hahn, Yvonne Hahn, Naghmeh Haji Beik, David Hammer, Michael Hansmeyer, Nikolai Happ, Bernd Heidlindemann, Jutta Heinze, Magdalena Hellmann, Anne-Kathrin Hellermann, Mirco Hirsch, Volker Helm, Lars Höffgen, Robert Hösl (Partner), Philip Hogrebe, Ulrike Horn, Michael Iking, Ina Jansen, Nils Jarre, Jürgen Johner (Associate), Leweni Kalentzi, Andreas Kimmel, Anja Klein, Frank Klimek, Julia Kniess, Uwe Klintworth, Alexander Kolbinger, Benjamin Koren, Tomas Kraus, Jonas Kreis, Nicole Lambrich, Jens Lehmann, Matthias Lehmann, Monika Lietz, Felix Morczinek, Philipp Loeper, Thomas Lorenz, Christina Loweg, Florian Loweg, Femke Lübcke, Tim Lüdtke, Lilian Lyons, Klaus Marten, Jan Maasjosthusmann, Petrina Meier, Götz Menzel, Alexander Meyer, Simone Meyer, Henning Michelsen, Alexander Montero Herberth, Felix Morczinek, Jana Münsterteicher, Christiane Netz, Andreas Niessen, Monika Niggemeyer, Monica Ors Romagosa, Argel Padilla Figueroa, Benedikt Pedde, Sebastian Pellatz, Malte Petersen, Jorge Picas de Carvalho, Philipp Poppe, Alrun Porkert, Yanbin Qian, Robin Quaas, Leila Reese, Constance von Rège, Chantal Reichenbach, Thorge Reinke, Ina Riemann, Nina Rittmeier, Dimitra Riza, Miquel Rodríguez (Associate), Christoph Röttinger, Guido Roth, Henning Rothfuss, Peter Scherz, Sabine Schilling, Chasper Schmidlin, Alexandra Schmitz, Martin Schneider, Leo Schneidewind, Malte Schoemaker, Katrin Schwarz, Henning Severmann, Nadine Stecklina, Markus Stern, Sebastian Stich, Sophie Stöbe, Stephanie Stratmann, Ulf Sturm, Stefano Tagliacarne, Anke Thestorf, Katharina Thielmann, Kerstin Treiber, Florian Tschacher, Chih-Bin Tseng, Jan Ulbricht, Florian Voigt, Maximilian Vomhof, Christof Weber, Lise Wendler, Philipp Wetzel, Douwe Wieërs, Julius Wienholt, Julia Wildfeuer, Boris Wolf, Patrick Yong, Kai Zang, Xiang Zhou, Bettina Zimmermann, Christian Zöllner, Marco Zürn

Client:

Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Germany; represented by ReGe Hamburg Project-Realisierungsgesellschaft mbH, Hamburg, Germany

General Designer:

Consortium PlanerArge Elbphilharmonie Hamburg:

– Herzog & de Meuron GmbH, Hamburg, Germany

– H+P Planungsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, Aachen, Germany

– Hochtief Solutions AG, Essen, Germany

Acoustics:

Nagata Acoustics Inc., Los Angeles / Tokyo, USA / Japan

General Contractor:

Adamanta Grundstücks-Vermietungsgesellschaft mbH & Co., Düsseldorf, Germany with Hochtief Solutions AG, Essen, Germany

Building Data:

Site Area: 10’540sqm / 113’452sqft

Footprint: 5’600sqm / 60’278sqft

Gross Floor Area: 120’383sqm / 1’295’792sqft

Building Length: West 21.60m / 71ft,; North 108.60m / 356ft; East 87.90m / 288ft; Southwest 125.90m / 413ft

Building Height: Kaispeicher 37.25m / 120ft (from water level to the plaza); Philharmonic Hall: 110m / 360ft; (from water level to the peak of the building), approx. 102m / 335ft above street level

Number of Levels: 26 floors

Comments are closed.