Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners . photos: © Ulrich Schwarz

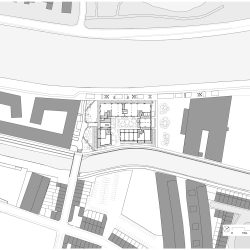

Vilvoorde is one of the Flemish cities characterized by industry on the outskirts of the Brussels metropolis. With around 45,000 inhabitants, it is located on the Brussels–Scheldt Maritime Canal. This represents an important transport canal for Belgium and at the same time holds great potential as a landscape element with its spacious layout. An attractive mix of existing industry and urban residential areas has developed along the canal, especially in Brussels. With the redevelopment of the eastern bank of the canal according to the master plan of the urban-planning firm BUUR, this development of Brussels continues in Vilvoorde accordingly. A LOCATION FULL OF CONTRASTS

The project “Waterzicht” is part of this new master plan called “De 4 Fonteinen.” It is right on the canal with a view of the 50-hectare De Drie Fonteinen park on the other side, which dates back to the late eighteenth century and is one of Belgium’s oldest landscaped parks. It was designed as an English landscape garden and creates a romantic atmosphere with its old trees. The project borders a very fragmented and rugged hinterland on the eastern side. Here some powerful, transformed industrial buildings are situated, on the one hand, and a large working-class area with small terraced houses, on the other. In addition, the small river Senne flows here, which is completely channeled within dam walls. Its banks were replanted as part of the redevelopment above the walls. In the south, the picture is completed by the ring road of Brussels, visible from afar, which crosses the canal at a distance of about 300 meters with the impressive 1,700-meter-long and 35-meter-high Vilvoorde viaduct.

ARCHITECTURAL URBAN PLANNING

How should new buildings react to such an urban space? And how can the architecture assert itself at all? What kind of city should be built here?

BUUR’s master plan envisaged a series of powerful architectures intended to enliven the generously designed public bank of the canal like a string of pearls, while at the same time mediating between the large-scale canal side and the smaller-scale hinterland. All the buildings form courtyards on the inside and serve as large structures on the outside. To the south of the project there was already a generously sized brick building by the architecture firm A2O, which corresponds exactly to this logic.

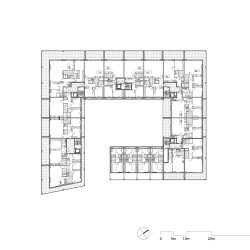

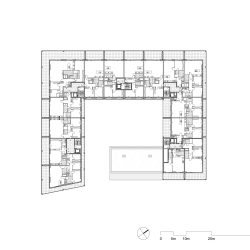

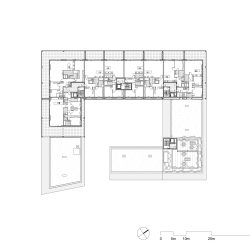

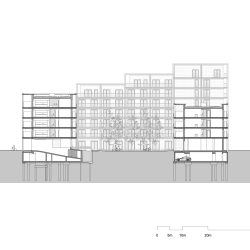

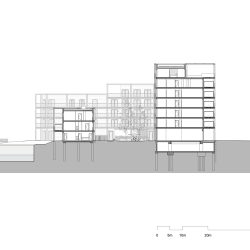

Various urban-planning requirements pertain to the location of the project Waterzicht, giving rise to a great deal of complexity. Along the canal, the building had to be at least five stories high. There is an eight-story elevation accent on the northern corner. On the Senne side, a maximum height of four floors and a volumetric fragmentation were desired to better connect with the workers’ housing.

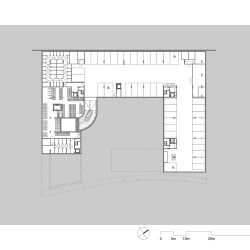

Programmatically, the ground floor facing the canal should be as lively as possible with shops and restaurants. In the area toward the Senne, living on the ground floor is possible. In addition, the Matexi development company wanted a couple of terraced houses facing the Senne, which typologically are diametrically opposed to the logic of multistory housing.

All of these circumstances created an extremely heterogeneous starting point for the architecture. The challenge then was to ensure a strong bond within this heterogeneity and to unite it as a consistent whole that goes beyond the mere sum of the individual fragments.

TERRACES AS A DESIGN STRATEGY

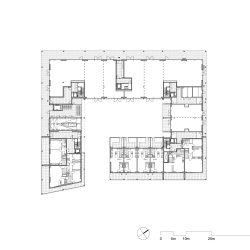

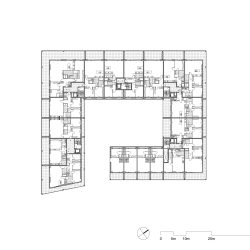

Programmatically speaking, the project Waterzicht is relatively simple at first. Shops and restaurants were only planned for the front area of the ground floor; otherwise there is an underground parking garage and apartments of different sizes developed primarily for sale. There are large, expensive apartments facing the canal with 3.5-meter-deep balconies created especially for the beautiful view of the water and the park on the opposite side. In the roof area, the apartments are designed to descend from north to south, each with terraces running all around on three sides. In addition to a sensible orientation toward the sun, the theme of the stairs responds to the urban-planning desire for a height accent in the north and transfers this concept to the lower parts of the building. Perpendicular to the canal are more affordable, medium-sized apartments. Located on the Senne side, in turn, are four terraced houses with double-height balconies and medium-priced apartments.

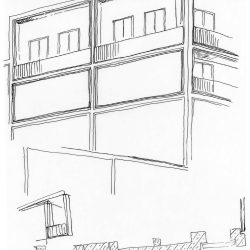

All façades, both outside the building and inside the courtyard, are combined with balconies or terraces, which vary greatly in terms of depth and respond differently to the respective living typologies and cardinal points. The spatial openness of the inner courtyard to the outside also creates a direct transition between the courtyard and the outer façade with balconies connecting the inside and outside accordingly. The encircling terraces as an exoskeleton in prefabricated concrete parts hold meaning as a strategically used architectural element that goes beyond the actual living quality. Typological and morphological differences, varying axis dimensions, partly double-height exterior spaces, et cetera, are combined to form a whole without restricting the freedom required for each part.

COLLECTIVE YARD

The volume of the building encloses a courtyard about 31 meters in length and 19 meters in width, which opens to the Senne on the southeast side. The courtyard is more vertically proportioned according to the volume of the building, especially on the northwest side, which fosters an urban impression. In order to avoid too narrow courtyard proportions and to reduce the vis-à-vis positioning of the apartments, the balconies in the courtyard are rather shallow, in some cases reduced to narrow French balconies.

A special element is created in the courtyard due to the garage entrance with bicycle parking spaces and the elevator, in combination with the entrance halls of the adjacent access cores. This gives rise to another situation where the courtyard opens up to the outside toward public space, allowing the courtyard to be experienced in its depth. The entrance hall, which is directly adjacent to the underground parking garage entryway, has large panoramic glazing, which makes the visual relationships and perspectives even more complex and diverse.

The greenery and the gravel paths in the courtyard engender a friendly, intimate, and homely atmosphere that invites use of this space.

MATERIALITY BETWEEN INDUSTRY AND CITY

With its façade materials, the project aims to bridge the seemingly contradictory worlds of the industry along the canal with its pollution on the one hand, and the stone city on the other. Gray limestone, high-quality aluminum windows that are thermo-lacquered in a bronze tone, steel-framed glass railings, and precast concrete elements are solid and robust materials, durable in the best sense of the word. With its reserved grayness and large window formats, the building radiates openness and calm elegance. At the same time, the gray also suits the Flemish sky.

Natural stone and concrete are both of a similar gray. This circumstance creates a large monolith, so that the project, in both size and shape, stands like a kind of rock in the landscape.

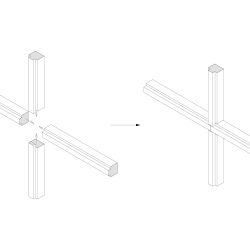

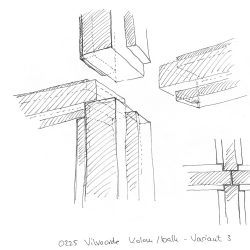

The concrete structure of the prefabricated terraces is designed in accordance with tectonic logic. Supports stand on beams, which in turn rest on supports, thus creating a logic that translates carrying and loads into an understandable visual language for the eye. In order to refine the concrete structure of beams and columns and make the building appear thinner, a rejuvenation of the external view of the elements was introduced. In this way, the concrete elements appear elegant even with slightly smaller spans. The connections between beams and columns lend character to the entire block as an industrial ornament.

RESPONSIVE LANDMARK

For Atelier Kempe Thill, the project Waterzicht initially represented the logical continuation of the typological experiments of residential buildings with spacious balconies all around, such as those envisaged in the City Palace project in the Nieuw Zuid neighborhood of Antwerp. Here, too, it was a matter of defining a housing typology for the twenty-first century that primarily links high-density urban living with as many suburban spatial qualities as possible. High residential density is combined with openness and lightness as a living atmosphere.

Due to the complex initial urban-planning conditions, however, something new was created: the building is a large sculptural object that has a strong identity and thus establishes its own context and a real identity. It is thus able to fulfill its role as a new strong link in the divergent context, and to make a substantial contribution to clarifying the urban-planning situation. It fabricates an island of city and urbanity within a fragmented periphery.

However, it is not a question of an autonomously set and merely self-referential prototype. Rather, it is a building that, through its architecture, responds sensitively to the different contexts and yet maintains its consistency. On the one hand, the architecture refers to the monumentality of the industry along the Brussels canal through its shape and size, which is also reinforced by the industrial construction methods used. On the other, due to the lower height and the morphological variation caused by the different residential typologies, there is a strong connection to the small scale of the hinterland to the east of the project.

Waterzicht is ultimately an architectural experiment in how much freedom and informality is allowed in building organization, and yet how much unity is needed to experience the project as a whole.

_

LANDMARK AT THE WATER: WATERZICHT

Vilvoorde, Belgium

2018–23

program urban plan: Housing with commercial ground floor

architects urban plan: BUUR – urban platform – evr architecten

landscape architect: LAND landschapsarchitecten

program: 68 apartments + 4 rowhouses + 886 m2 commercial space

with onderground parking garage

address: Steenkaai, 1800 Vilvoorde

architects: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners

client: Matexi

Process:

tender: April 2018

start commission: May 2018

start execution: July 2020

date delivery: December 2022

Building:

site area: 3.440 m2

building size: 15.094 m2 (gross floor area)

12.963 m2 (gross floor area) above ground incl. terraces

2.131 m2 (gross floor area) underground

building volume: ca. 49.000 m3 (gross volume)

building budget: € 17.800.000,-

building costs: € 19.196.000,-

(incl. technical installations excl. vat)

costs /m2 1.271€ /m2

budget /m3 391€ /m3

Design team project:

Team tender: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners, Rotterdam NL

André Kempe, Oliver Thill, Kim van Kempen

Team project: Atelier Kempe Thill architects and planners, Rotterdam NL

André Kempe, Oliver Thill with

Laura Paschke

Saskia Hermanek

Nynke Bergstra

Jurriaan Blom

Philip Haak

Marc van Bemmel

Maria Dau

Kento Tanabe

structural engineer: Group D engineering

building services engineer: Ingenium / Industrium

Acoustic engineer: D2S International nv

Renderings POLYGON België

Photographer: Architektur-Fotografie Ulrich Schwarz

Ulrich Schwarz

Ein Standort voller Kontraste Vilvoorde ist eine der durch Industrie geprägten flämischen Städte am Rand der Brüsseler Metropole mit ca. 45.000 Einwohnern und liegt am Seekanal Brüssel-Schelde. Dieser stellt einen für Belgien wichtigen Transportkanal dar und besitzt mit seiner großzügigen Anlage gleichzeitig ein großes Potenzial als landschaftsräumliches Element. Entlang des Kanals hat sich vor allem in Brüssel ein reizvoller Mix aus Industrie und städtischen Wohngebieten entwickelt. Mit der Neuentwicklung des östlichen Kanalufers nach dem Masterplan des Städtebaubüros BUUR setzt sich diese Brüsseler Entwicklung in Vilvoorde fort. Das Projekt Waterzicht befindet ist Bestandteil des neuen Masterplans„De 4 Fonteinen“. Es liegt direkt am Kanal. Am gegenüberliegenden Ufer befindet sich der 50 Hektar große Park „De Drie Fonteinen“, der aus dem späten 18. Jahrhundert stammt und einer der ältesten Landschaftsparks von Belgien ist – ein englischer Landschaftsgarten mit altem Baumbeständen und romantischer Atmosphäre. Auf der östlichen Seite hingegen grenzt das Projekt an ein ausgesprochen fragmentiertes und schroffes Hinterland. Hier findet man einerseits einige transformierte kraftvolle Industriegebäude, andererseits ein großes Viertel mit kleinen Reihenhäusern für Arbeiter. Darüber hinaus fließt hier das vollständig kanalisierte Flüsschen Senne, dessen Ufer im Rahmen der Neuentwicklung oberhalb der Wände neu bepflanzt wurden. Im Süden wird das Bild durch die weithin sichtbare Ringautobahn von Brüssel komplettiert, die, ungefähr 300 Meter entfernt, mit dem beeindruckenden 1700 Meter langen und 35 Meter hohen Vilvoorde-Viadukt den Kanal überquert. Architektonischer Städtebau Wie sollen neue Gebäude auf einen solchen Stadtraum reagieren, und wie kann die Architektur sich hier behaupten? Was für eine Art von Stadt soll hier entstehen? Der Masterplan von BUUR sieht eine Reihe kraftvoller Architekturen vor, die, einer Perlenkette gleich, die großzügig entworfene, öffentliche Uferkante des Kanals beleben sollen und die gleichzeitig in der Lage sind, zwischen der großmaßstäblichen Kanalseite und dem kleinteiligeren Hinterland zu vermitteln. Die Gebäude bilden in ihrem Inneren allesamt Hofräume aus und agieren nach außen als großmaßstäbliche Objekte. Südlich des Projektes befindet sich bereits ein großes Backsteingebäude des Büros A2O, das genau dieser Logik entspricht. Für den Standort des Waterzicht-Projektes gibt es städtebaulich verschiedene Anforderungen von großer Komplexität. Entlang des Kanals soll das Gebäude mindestens fünf Geschosse hoch sein, mit einem Höhenakzent von acht Geschossen auf der nördlichen Ecke. Zur Senne ist eine Höhe von maximal vier Geschossen und eine volumetrische Fragmentierung gewünscht, um besser an die Reihenhaussiedlung anzuschließen. Zum Kanal hin soll das Erdgeschoss möglichst mit Läden und Restaurants belebt sein. Im Bereich Richtung Senne ist im Erdgeschoss auch Wohnen möglich. Hinzu kommt, dass die Entwicklungsgesellschaft Matexi zur Senne hin ein paar Reihenhäuser wünscht, die typologisch der Logik eines Geschoßwohnungsbaus diametral entgegensteht. All diese Umstände erzeugen eine äußerst heterogene Ausgangssituation für die Architektur. Die Herausforderung besteht darin, für eine starke Bindung zu sorgen und ein konsistentes Ganzes zu schaffen, das mehr als die Summe einzelner Fragmente ist. Terrassen als Entwurfsstrategie Das Waterzicht-Projekt ist programmatisch zunächst relativ einfach aufgesetzt: Läden und Restaurants sind lediglich an der Vorderseite des Erdgeschosses vorgesehen. Es gibt eine Tiefgarage und vor allem für den Verkauf entwickelte Wohnungen unterschiedlicher Größe: Zum Kanal hin sind es große, teure Wohnungen mit 3,5 Meter tiefen Balkonen, mit schöner Aussicht auf den Kanal und den Park. Im Dachbereich sind die Wohnungen von Norden nach Süden abtreppend mit jeweils auf drei Seiten rundumlaufenden Terrassen entworfen. So wird einerseits eine sinnvolle Ausrichtung zur Sonne möglich, andererseits entsteht im Norden der gewünschte städtebauliche Höhenakzent. Im auf den zum Kanal zulaufenden Gebäudeteil befinden sich preiswertere mittelgroße Wohnungen. Auf der Seite der Senne stehen vier Reihenhäuser mit doppelt hohen Balkonen sowie mittelteuren Appartements. Alle Fassaden, sowohl nach außen als auch zum Hof, sind mit Balkonen bzw. Terrassen kombiniert. Diese variieren in ihrer Tiefe stark und reagieren unterschiedlich auf die jeweiligen Wohntypologien und Himmelsrichtungen. Auch entsteht durch die räumliche Offenheit des Innenhofes nach außen ein direkter Übergang zwischen Hof und Außenfassade mit entsprechend zwischen innen und außen verbindenden Balkonen. Die umlaufenden Terrassen als Exoskelett in Betonfertigteilen haben über die eigentliche Wohnqualität hinaus eine Bedeutung als strategisch eingesetztes architektonisches Element. Typologische und morphologische Unterschiede, variierende Achsmaße, teils doppelt hohe Außenräume usw. werden zu einem Ganzen verbunden, ohne die für jeden Teilbereich notwendigen Freiheiten einzuschränken. Kollektiver Hof Das Gebäudevolumen umfasst einen Hof von ungefähr 31 Metern Länge und 19 Metern Breite, der allerdings nicht vollständig geschlossen, sondern an der Süd-Ostseite, zur Senne hin, offen ist. Er ist vor allem zur Nord-West-Seite durch die Gebäudevolumen eher vertikal proportioniert, wodurch ein urbaner Eindruck entsteht. Um eine zu schmale Hofproportion zu vermeiden sowie das Vis-a-Vis der Wohnungen zu reduzieren, sind die Balkone im Hof weniger tief, zum Teil werden sie hier auf schmale Austritte reduziert. Ein besonderes Element im Hof stellt die Garageneinfahrt mit Fahrradabstellplätzen sowie dem Lift in Kombination mit den Eingangshallen der angrenzenden Erschließungskerne dar. Hierdurch entsteht eine Öffnung des Hofs nach außen zum öffentlichen Raum hin, der den Hof in seiner Tiefe erlebbar macht. Die direkt an die Tiefgarageneinfahrt angrenzende Eingangshalle hat eine große Panoramaverglasung, die die Sichtbeziehungen und Durchblicke noch komplexer und vielfältiger gestaltet. Die Bepflanzungen und die Kieswege im Hof erzeugen eine freundliche, intime und wohnliche Atmosphäre, die zur Nutzung des Hofes einlädt. Materialität zwischen Industrie und Stadt Mit den Fassadenmaterialien versucht das Projekt, eine Brücke zwischen den scheinbar gegensätzlichen Welten der Industrie entlang des Kanals, mit deren Umweltverschmutzung, und der steinernen Stadt zu schlagen. Grauer Kalkstein, hochwertige, in einem Bronzeton thermolackierte Aluminiumfenster, Glasgeländer in Stahlfassung und Betonfertigteile sind solide und robuste Materialien, dauerhaft im besten Sinne. In seinem zurückhaltenden Grau und den großen Fensterformaten strahlt das Gebäude Offenheit und ruhige Eleganz aus. Gleichzeitig passt dieses Grau auch zum flämischen Himmel. Naturstein und Beton sind beide in einem ähnlichen Farbton. So wirkt das Projekt sehr monolithisch und steht wegen seiner Größe und Form wie eine Art Felsen in der Landschaft. Die Betonstruktur der Terrassen aus Fertigteilen ist in tektonischer Logik entworfen. Balken ruhen auf Stützen, auf den Balken stehen wiederum Stützen. Das erzeugt eine Logik, die das Tragen und das Lasten für das Auge in eine verständliche visuelle Sprache übersetzt. Um die Betonstruktur aus Balken und Stützen zu verfeinern und sie dünner erscheinen zu lassen, wurde eine Verjüngung der Außenansicht der Elemente eingeführt. Auf diese Weise wirken die Betonelemente selbst bei etwas kleineren Überspannungen elegant. Die Verbindungen zwischen Balken und Stützen geben dem gesamten Block als industrielles Ornament Charakter. Reagibles Landmark „Waterzicht“ stellt für Atelier Kempe Thill zunächst die logische Fortsetzung der typologischen Experimente von Wohngebäuden mit großzügigen und umlaufenden Balkonen dar, wie sie zum Beispiel bei dem Projekt Stadtpalast in Antwerpen Nieuw Zuid begonnen wurden. Es geht auch hier um das Definieren einer Wohntypologie für das 21. Jahrhundert, die vor allem städtisches Wohnen in hoher Dichte mit möglichst vielen suburbanen räumlichen Qualitäten kombiniert: hohe Wohndichte mit Offenheit und Leichtigkeit. Aufgrund der komplexen städtebaulichen Ausgangsbedingungen entsteht hier jedoch etwas Neues: Das Gebäude ist ein großes skulpturales Objekt, das eine starke Identität besitzt und damit einen ganz eigenen Kontext und eine wirkliche Adresse erschafft. So kann es seiner Rolle als neues starkes Bindeglied in einem divergenten Kontext gerecht werden und substanziell dazu beitragen, die städtebauliche Situation zu klären. Es erzeugt eine Insel von Stadt und Urbanität innerhalb einer fragmentierten Peripherie. Es handelt sich jedoch nicht um einen autonom gesetzten und lediglich auf sich bezogenen Prototyp. Es ist vielmehr ein Gebäude, das in der Lage ist, aus seiner Architektur heraus sensibel auf die unterschiedlichen kontextuellen Situationen zu reagieren und dennoch seine Konsistenz zu wahren. Die Architektur referiert durch ihre Form und Größe einerseits an die Monumentalität der Industrie entlang des Brüsseler Kanals, was auch durch die eingesetzten industriellen Baumethoden verstärkt wird. Andererseits entsteht durch die geringere Höhe und die morphologische Variation aufgrund der verschiedenen Wohntypologien ein starker Bezug zur Kleinmaßstäblichkeit des Hinterlandes östlich des Projektes. „Waterzicht“ ist ein architektonisches Experiment dahingehend, wie viel Freiheit und Informalität in der Gebäudeorganisation möglich sind und wie viel Bindung es braucht um das Projekt dennoch als ein Ganzes zu erfahren.