ALT. CORP. photos: © Vlad Patru

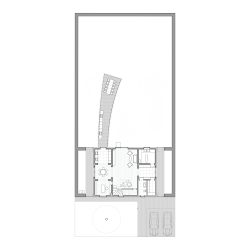

The house in Dumbrava Vlăsiei establishes an approach whose main focus is emphasizing two fundamental elements that make up a suburban home: the rooms and the garden. The project unfolded based on this simple limitation: the house should contract itself, freeing up as much land as possible and making room for “Grădina cu camere” (The Garden with Rooms).

“Grădina cu camere” is a three-storey single-family home built as part of a suburban gated community found at approximately 30 km. North of Bucharest’s city center. The project is based on the winning entry of a design competition addressed to young architects and organized by a private investor („Imagine Dumbrava Vlăsiei”, 2018).

The site and its situation were somewhat remote from the so-called “local tradition” of single-family homes. Designing a house in the absence of any facts regarding its inhabitant, as well as the lack of any built vicinity or any kind of enclosures whatsoever, triggered the search for what is truly specific to having a house with a courtyard – the garden, the primary attribute of a “house built on the ground”, an intimate enclosure cut out of a homogenous suburban lawn.

The fact that the project was conceived in the absence of an actual client, other than the investors, suggests that the built house itself is rather the sequence of a functional becoming whose finality is to be postponed until the appearance of those who will inhabit it. Such an expectation causes the idea of “dwelling” to be temporarily suspended.

Nevertheless, the apparent uncertainty regarding the natural (and inevitable) utility of the house should not be perceived as a shortcoming; the absence of a real client, of furniture or garden arrangements, can be seen as signs of a privileged moment. Therefore, the house does not seem to have what we call “function”, being more of an assembly of spaces without a certain destination. Such a depersonalization, imposed by the absence of the aforementioned elements, becomes an opportunity to describe it without having a measuring instrument to quantify its proportions.

This impersonal aspect of the project’s context is, in the end, not a limitation, but a quality providing a clarifying point of view, a determining factor that sets the ground for the house’s pristine character as pure/abstract construction.

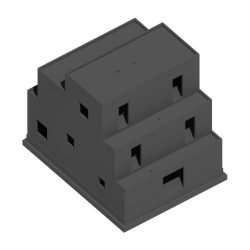

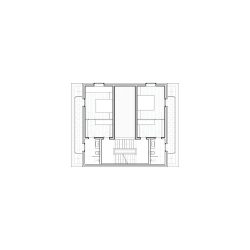

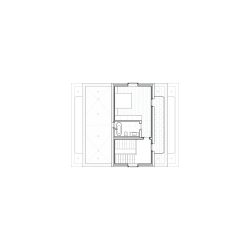

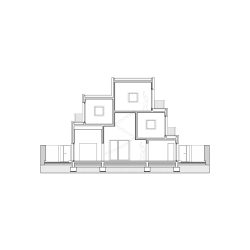

A certain constructive rationality dictated how things were to be built, primarily by gathering all the rooms on the smallest possible portion of the plot and subsequently stacking all of them one atop another in a ziggurat-like arrangement. Consequently, the living room became an interior cavity determined by the outer limits of the plot, while the staircase acted as a buttress-like supporting element.

This disposition also determined the structure of the project: the geometry of the overlapping rooms claimed concrete as the only material capable of holding the building upright. The construction thus became a whole, a continuum of 15 cm. reinforced concrete both vertically and horizontally. The only exception to this homogeneity being the metal structure of the pavilion that “dives” outwards from the kitchen and belongs to the garden rather than the house.

The house’s relationship to the site is, in the end, a successive series of pseudo-parametric equations, reducing any whims or aesthetic affinities to the mere juxtaposition of constructive facts that consolidate the rather abstract overall appearance of this white and robust artefact.

_